|

6. A contemporary portrait of Catherine the Great

|

|

|

|

6. A contemporary portrait of Catherine the Great

She issued a parallel charter to the cities. Together, they fixed the form of local government and much of provincial social and political life until the 1917 revolution. The nobles became the only estate to have guaranteed rights, and this fact meant that serfdom became even more arbitrary: serfs had no legal protection against abuse. Russia was now run by a ruling class with its own defined rights, with a Europeanized culture and complete power over the persons of its serfs. This internal cultural and social gulf defined Russian life for the next century. The serfs, for their part, were perfectly capable of discerning that, while they still had state obligations, their superiors had none.

The brief reign of Emperor Paul (r. 1796–1801) illustrated what happened when an Emperor broke the convention that he should rule with the consent of the elite. Paul took the view, which would have been applauded by most peasants, that the nobles’ privileges were unjustified. He abolished their exemption from state service, closed down their provincial associations, and instead appointed local officials himself. He decreed that their estates should be taxed on the same basis as peasant land. He ended their freedom from corporal punishment, and curtailed their right to travel abroad and to receive foreign literature. At the same time, he gave peasants the right to petition him personally about mistreatment at the hands of their lords.

There is little doubt that Paul’s personality was unbalanced. He was given to sudden changes of mood and uncontrollable attacks of rage, when he would insult even his highest officials and advisers. The same, though, had been true of Peter the Great. In 1801, however, a group of Guards officers, led by the governor‑ general of St Petersburg, deposed Paul, with the consent of his son, Alexander. They then went on to murder him – something to which Alexander had not consented. Paul’s innovations were then quietly retracted.

Alexander (r. 1801–25) was well aware of the injustices Paul had tried in his clumsy way to rectify, but he took a very different approach to them. Up to the end of the 18th century, Russia’s leaders assumed that Russia would create for itself a ‘regular’ state similar to those evolving in the other European powers. Alexander I began his reign in this spirit, elaborating proposals to consolidate the rule of law and introduce representative institutions. But he faced an intractable dilemma. He could proceed by enhancing the freedoms of the nobility: but that would imply augmenting their privileges and intensifying social inequality. Or he could try to extend civil rights more broadly to the population as a whole: but that could be accomplished only by overriding the nobles and thus strengthening autocracy. In the course of his reign, he made serious plans in both directions, but brought neither to fulfilment.

In the end, Alexander’s most durable reform was the creation of functional ministries, each headed by a single minister who took responsibility for its work. This novelty, derived from European models, did something to introduce order and system into government. However, since there were no regular cabinet meetings and no prime minister, the task of coordinating government fell as before on the Emperor, consulting with individual ministers; this arrangement thus retained personal relationships at the heart of government. Moreover, the Ministry of the Interior was responsible for policing the entire empire and for overseeing all provincial institutions; it was thus much larger than any other, and its priorities tended to overshadow other governmental functions.

|

|

|

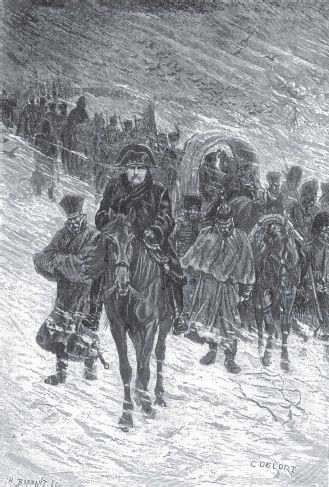

The war against Napoleon

Russia’s vulnerability, but also the geopolitical resources at its disposal, were dramatically illustrated by the war against Napoleon in 1812. When it invaded, the Grande Armé e was larger and more experienced than the Russian army. The only way to deny it victory was to retreat indefinitely, avoiding major battles and making use of Russia’s spaces and (eventually) severe climate to wear it down. Russia could mobilize men and resources from a rich and diverse reserve of food, raw materials, equipment, and manpower – though only slowly because of the distances. Yet endless retreat entailed terrible suffering, the destruction of homes, equipment, animals, and crops, the demoralization of both the civilian and military population. No one dared to announce this strategy openly, since it implied such horrific sacrifices. On the contrary, Alexander and his commander, Barclay de Tolly, originally declared their intention to retreat only a certain distance, to fortified lines where they hoped they could make a stand. Each time the Russian army reached such a line, however, Napoleon proved too threatening, and after skirmishes it resumed its retreat.

Eventually, Alexander decided the army had to make a stand before Moscow, and to implement his decision appointed a commander with an impeccably Russian surname, Mikhail Kutuzov, hero of Catherine’s wars. The result was the huge Battle of Borodino, technically a Russian defeat, after which the Grande Armé e resumed its advance, but in a weakened condition. Kutuzov decided that his forces could no longer defend Moscow and therefore abandoned the city – which was soon consumed by fire. Napoleon was appalled at the spectacle: ‘This is a war of extermination’, he exclaimed, ‘a terrible strategy which has no precedents in the history of civilisation! . . . What ferocious determination! What a people! ’ He still assumed he would soon receive envoys from the Tsar, suing for peace. But no one came to treat with him, and eventually he decided it was impossible to spend the winter in a devastated city.

On the miserable and seemingly endless march westwards out of Russia, the dwindling Grande Armé e was constantly harassed by guerrilla forces, small detachments which would suddenly emerge from the forest, kill stragglers and seize supplies, then vanish again. They consisted of peasants, though always under the command of regular officers. Alexander was nervous of mobilizing peasant volunteers, since he rightly assumed they would want to be freed from serfdom as a reward for doing their civic duty. Indeed, there were some disturbances where peasants tried to volunteer and resisted being turned away by recruiting sergeants.

|

|

|