|

Text 1. Early British music

|

|

|

|

Main READING activities

1. Read Text 1. Get ready to answer the questions and discuss the text.

TEXT 1. EARLY BRITISH MUSIC

There is a commonly accepted misconception that the English are not a musical people, that England is the land that cares little for music. But this is not true. Even in the XV century, John Dunstable (1385 – 1453) achieved the widest reputation among several important composers. English music of that time stands by itself, and has not always been justly appreciated. Its isolation was due primarily to geographical reasons, but also to England’s peculiar relations to the Papacy. The neglect of the subject has resulted from the difficulty of getting at the documents, which are now better known. The more the story is studied, the more interesting and even astonishing it becomes.

In the second half of the XV century English music suffered a check, perhaps because of the unsettled conditions during the Wars of the Roses. But even then some interest was indicated by the maintenance of the Chapel Royal (flourishing from at least 1465), by the conferring of musical degrees at both Oxford and Cambridge (from 1463), by the number of monastic and cathedral choirs and organs, by the chartering of a monopolistic Minstrels’ Guild (1469), and by popular interest in singing of all kinds.

The Tudors were all music-lovers, and during the reigns from Henry VII onward the Chapel Royal remained the chief rallying point for musicians, a model and incentive to cathedral and private establishments, and an object of astonished admiration from foreign visitors. As the century went on, English players were more and more drafted into service on the Continent, even when the existence of good English compositions was but slightly known.

In England the dramatic form that led toward the opera was the “masque”, originally imported from Italy in the XVI century, but specially developed by English poets. This was a piece of private theatricals in which members of high society in disguise (whence the name) acted out a mythological or other fanciful story with dialogue and declamation, much dancing, elaborate scenic effects and, as time went on, considerable singing and incidental pieces for instruments. Throughout the whole century almost all leading English composers wrote masque music, and thus gradually the musical masque became important (sometimes under the Italian name “opera”).

Thereafter, although works of high quality were written, English music was of mainly local importance, and influences tended to run in the other direction, from Italy and France, producing such English versions of Continental developments as the English madrigal. The word “madrigal” came from the Troubadours and meant originally a pastoral song, but in later usage it was applied to any lyric poem of decided artistic value. Its musical sense followed when such poems were taken as texts for vocal treatment.

In the XVI century England deserves credit for much progress peculiarly her own. She seems to have led the way in writing for keyboard instruments. Her development of counterpoint early in the century was distinct, and quite as remarkable. In the remodeling of styles under the influence of Protestantism she made an original combination of polyphony with the new materials of Protestant liturgies. The English cultivation of the madrigal and its relatives was strikingly original.

|

|

|

The historic importance of the madrigal is evident. It raised secular music to honor and afforded a chance for genius to exercise itself in fields otherwise untouched. Although essentially polyphonic, it really prepared the way for other vocal forms, even for dramatic monodies and arias, since it revealed the expressive possibilities of melody. The English development of the madrigal was prompt and rich, but marked by an instinctive effort to merge the madrigal proper with the lighter and gayer styles of the part-song and the dance.

In many cases competent composers wrote little else, so that at the opening of the XVII century the English school really devoted itself to this form. The most famous composers of this period should be given here:

John Sheppard, first a choirboy at St. Paul’s, London, in 1542 became organist at Magdalen College, Oxford, and from 1551 was in the Chapel Royal. He left services, motets and anthems.

Richard Edwards was both a poet and a musician of high order. From 1561 he was Master of the Chapel Royal, a post then involving dramatic as well as musical gifts. His madrigals are famous.

Robert Whyte was highly esteemed in his time, but strangely forgotten afterwards. He left numerous motets and anthems, with some instrumental fantasias, all showing great ability.

William Byrd became organist at Lincoln in 1563 and was in the Chapel Royal from 1570. His works include masses, motets, anthems, psalms, madrigals, songs and remarkable virginal-pieces, including some true variations. As an instrumental writer he was long unrivaled.

Thomas Morley, a pupil of Byrd, entered the Chapel Royal in 1592, after being for a time organist at St. Paul’s, and succeeded to Byrd’s monopoly in 1598. His canzonets, madrigals and ballets constitute the best of his work, though his instrumental pieces and limited sacred music are also notable. His theoretical treatise (1597) was influential.

John Dowland was exclusively a secular composer, and famous as a virtuoso upon the lute. Partly because of his Catholic associations in early life, he spent much time abroad, visiting France, Germany and Italy. On returning to England, he held two or three positions, the last as court-lutist. His madrigals have remained in use to the present.

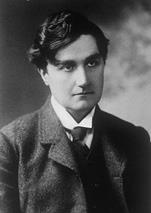

| The one master with both dramatic and musical gifts was the extraordinary Purcell, whose fertile originality, in spite of the brevity of his career, brought the century to a brilliant close. Henry Purcell was one of England’s most important and original Baroque composers. He worked during the reign of three monarchs and composed odes |  Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell

|

(musical poems), sacred anthems, songs, opera, and chamber music.

Making up for the lack of travel by intuition and assiduous study, he seized upon the finest points in the Italian style, combined them with some features (especially in choral writing) strangely neglected, and applied them to the treatment of plots that were essentially strong.

|

|

|

His many-sidedness is remarkable, since he worked with equal power in stately and thoughtful church music, in festal odes and tributes, in purely chamber music, and in every grade of opera. The culmination of his dramatic efforts came when he was joined by Dryden as a poetic collaborator. Even before he died, his superiority was well discerned, while now he appears as one of the most creative geniuses of the century. It is a tragedy of history that his career was not only so short, but so utterly devoid of consequence.

After Purcell no native English writer appeared to fill his place or continue his work. The XVIII and XIX centuries were in general a low point in the vitality of native English music, unless George Handel is considered to have become an English composer, so completely was his music absorbed into the native tradition. England may have been very backward indeed in the creation of symphonies and concertos, but a nation so eagerly vocal can hardly be described as being pathetically unmusical. And if London, after Handel, produced no great music, it could heartily welcome such music, and if necessary, was ready to commission work from famous composers, when they were left ignored by their own Central Europe, because in England there were certainly persons anything but indifferent to music.

The declining school of English church music has nothing to show in the XVIII century. The taste for services and anthems of the “verse” or solo sort, which set in powerfully towards the end of the XVII century, continued, though for a time it was slightly offset by the genius of a few worthy choral writers, mostly in the Chapel Royal.

Among the more prolific anthem-writers were James Hawkins, organist at Ely from 1682, with 75 verse and full anthems, Vaughan Richardson, organist at Winchester from 1693, with 21 anthems, John Weldon, pupil of Purcell and organist at Oxford from 1694 and named “composer”, and John Goldwin, with 24 anthems.

Besides, the XVIII century delighted in the theatre and entertainment in general. The main entertainment was ballad opera, which usually offered as much spoken dialogue as it did songs and dances. This was an amusing, often satirical, play in which well-known popular songs or similar numbers were strung together by a spoken dialogue into a loosely connected story. Essentially it was an inferior sort of comic opera, and its popularity from 1728 interfered with the success of more serious music. Most of the writers in this style, however, contributed also to others. In all, about 45 ballad-operas were produced in a little over 15 years.

Although during the opening decades of the XIX century the interchange of music and musicians between England and the Continent noticeably increased in volume and frequency, English musical production was still almost without influence upon the great currents of progress. The three main lines of activity were the drafting of numerous ballad-operas and operettas, often adapted freely from larger Continental works so as to feed the popular appetite for dramatic amusement, the production of many glees and songs, and the supply of music for the Anglican church service. Yet, though comparatively isolated, English musical interest was considerable in amount, often discriminating and alert in quality and, in some few cases, marked by original power.

The connection of England with the rise of pianism and its literature has already been noted. It also shared promptly in the Bach revival on its organ side. It contributed some excellent instrumentalists and singers. And it stood ready to extend enthusiastic greeting to such geniuses as Weber and Mendelssohn.

The first visit of the latter in 1829 marked the beginning of a new era in the growth of musical life in England. His magnetic influence did much to bring the English public into touch with some phases of the musical life of Europe and to enforce a high standard of technical correctness in both composition and performance. Contact with Continental music was steadily increased through the English students who now began to frequent Leipzig for training. The Mendelssohnian influence inevitably produced a general tendency merely to imitate his style, accepting it as representing all that was good in musical art.

|

|

|

Among the notable institutions founded in this period the following may be mentioned:

The Birnzbighallt Festivals from 1796 were held triennially, continuing with but one exception to the present time. With their firm establishment they steadily broadened from their original exclusive devotion to Handel’s choral works, becoming one of the factors in the stimulation of general musical taste.

The Concentores Sodales was a society founded by Horsley in 1798 to promote practice and production along lines like those of the earlier Glee and Catch Clubs. It continued until 1847.

The Philharlnonic Society began in 1813 and became at once the centre of instrumental music of the highest order for the Kingdom. For a long period its rehearsals and concerts were conducted by the principal members in turn.

As to the composers of the XIX century, we should remember that the musical climate of Victorian England was unfavourable to bold and daring composition.

Michael William Balfe was the most fertile of the opera-writers. Coming to London in 1823, he worked first as violinist and singer, with study under good teachers. His stageworks numbered about 30. They are over-facile and shallow, but abound with taking melodies and are often scored with some skill.

Other names in this middle period that might be mentioned are William Vincent Wallace, who wrote much salon music for the piano and operas, George Alexander Macfarren, who was one of the best-trained and most competent composers of the period. From 1834 he taught in the Royal Academy and from 1876 was its principal. His works included 8 symphonies, 7 overtures, several concertos, good chamber music, piano-sonatas, operas and other stage-works, 4 oratorios, 6 cantatas, part-songs, duets and songs, as well as several theoretical treatises.

The first important British composer in two hundred years – that is, since the death of Purcell – was Sir Edward Elgar. Elgar loved England, her past, her people, her countryside and he responded to her need for a national artist. By inclination he was a natural musician of great invention. “It’s my idea,” he said, “that music is in the air all around us, the world is full of it and it is important that you should take as much of it as you wish.” What he took was not always distinguished, but he managed to transform it into something that shone with all the brilliancy of the post-romantic orchestra. He also composed oratorios, chamber music, symphonies, and instrumental concertos.

Frederick Delius comes next. He found it essential that music should be the expression of a poetic and emotional nature, and indeed Delius’s music reminds us of the English landscape and its seasons: the freshness of spring, the short-lived brilliancy of summer, the sadness of autumn. He was regarded as the most poetic composer born in England.

| The English renaissance in music was heralded by an awakening of interest in the native song and dance. Out of this interest came a generation of composers. The most important figure among them was Ralph Vaughan Williams, the representative of English music on the international scene. He suggested that a composer in England should |  Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams

|

draw an inspiration from life around him. His love of folk tunes was part of an essentially melodic approach to music. Williams held the attention of the world due to his superb command of the grand form.

|

|

|

Ralph Vaughan Williams is a central figure in British music because of his long career as teacher, lecturer and friend to so many younger composers and conductors. His writings on music remain thought-provoking, particularly his oft-repeated call for all persons to make their own music, however simple, as long as it is truly their own.

William Walton and Benjamin Britten dominated this generation of composers. Walton’s style was influenced by jazz music, and is characterized by rhythmic vitality, bittersweet harmony, sweeping Romantic melody and brilliant orchestration. His output includes orchestral and choral works, chamber music and ceremonial music, as well as notable film scores. His earliest works brought him notoriety as a modernist, but it was with orchestral symphonic works that he gained international recognition.

Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten

| Britten was the most dominant and prolific XX-century composer. His music influenced every part of British musical life. Britten was an accomplished pianist, frequently performing chamber music and accompanying lieder and song recitals. He reinvented British opera for the XX century and, as a conductor, performed the music of many composers, as well as his own. |

For many musicians Britten’s technique, broad musical and human sympathies and ability to treat the most traditional of musical forms with freshness and originality place him at the head of composers of his generation.

(from “The History of Music”)

2. Explain the meaning of the following words and word-combinations from the text.

| madrigal concerto oratorio treatise motet | to commission work ballad opera chamber chorus liturgy overture | canzonet anthem lieder chamber music masque music |

3. Answer the questions

1) What are the reasons for the misconception that the English are not a musical people? Comment on the reasons for which English music of the XV century hasn’t been justly appreciated.

2) What tendencies existed in English music in the medieval period? Characterise the main musical forms of that period.

3) Comment on madrigal as a specific musical form in England. Specify its historical and artistic value and peculiarities of its development in the XVII century.

4) Speak on Henry Purcell’s contribution to developing English musical style.

5) Characterise the XVIII and the XIX centuries in the context of native musical tradition. Which composers could be regarded as most absorbed into it?

6) Name characteristic features of interchange of music and musicians between England and the Continent in the XIX century.

7) Characterise cultural and historical background of Britain in the Victorian age and its influence on musical life.

8) Why is the beginning of the XX century considered to be the English renaissance in music? What composers heralded this shift in the world reputation of music in Britain?

4. Read Text 2, point out words and expressions connected with music and musicians. Give a summary of the text.

|

|

|