|

TEXT 1. British Theatre History

|

|

|

|

Theatre, as we know it, did not exist when the first millennium dawned, but that does not mean that there was no drama. In fact, the bards of the Dark Ages who told legends such as Beowulf, were undoubtedly actors, performing rather than simply singing.

As we progress into the second millennium, we learn of a variety of plays which were performed in churches. There was, for instance, a resurrection play at Beverley, performed in a churchyard by masked actors, around 1220, and we also know of two XII century Anglo-Norman plays – Adam and La Seinte Resurreccion.

| So-called “Saints Plays” were also popular. The earliest was performed at Dunstable in Bedfordshire in the XII century and was about St Katherine, but, of all these plays, only two have survived, both from East Anglia. Best known of all medieval dramas are the Mystery Cycles. The earliest is York plays, which are mentioned as being performed as early as 1376. They |  Engraving depicting an early Chester Mystery Play

Engraving depicting an early Chester Mystery Play

|

consisted of 48 pageants which were performed on a single day, Corpus Christi (the first Thursday after Trinity Sunday),whereas the 24 pageants of the Chester Cycle were performed over three days, the Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday of Whitsun week.

The Mystery Plays were an attempt to tell the story of the Bible, beginning with the Creation and ending with the Harrowing of Hell and the Last Judgment

Then the Morality Plays appeared. The earliest of the Morality plays was The Castle of Perseverance (XV century), although the best known is Everyman which was first printed around 1510. These plays are allegories which are intended to show the people how they should live their lives and not succumb to temptation and the devil.

The XVI century was the great watershed of British theatre. One of the most significant new developments was the rise of the professional actor. In the liturgical dramas of the preceding centuries monks, nuns and priests were the performers. What paved the way for the development of professional theatre was the love of the Tudor monarchs for display. Henry VIII had his own troupe of actors – four men and a boy – who were skilled in quick costume changes and playing a number of parts.

It was, however, the development of the actual theatre building which was to change the whole course of British theatre. By the last quarter of the XVI century theatre companies had begun to be formed, usually under the patronage of aristocrats. These were made up of professional actors and played in two totally distinct kinds of venue: the homes of their patrons, where they played to the aristocracy, and inn yards, where they played to the populace. They were paid in two distinct ways, by their patron for their work for him and by collections among the inn yards audiences, the latter not being a very sure way of covering costs, let alone making a profit!

In 1574 the law changed to allow performances on weekdays and this led directly to the building of the very first theatre. The first was simply called The Theatre and was built by master carpenter James Burbage, who had professional acting experience himself. It was built outside the City of London in Shoreditch. Other theatres followed remarkably quickly. These great Elizabethan playhouses were open to the elements. There was a roof over the stage and those who sat in the seats had roofs over their heads, but the groundlings, those who stood in the open well in front of the stage, had no such protection. The indoor theatres, however, were private theatres, in some ways similar to the performances given in aristocratic mansions, but built for the purpose.

|

|

|

So the playhouses were built, but there were no plays! Or, at least, the repertoire was very small indeed. And then, suddenly, there was an explosion of new writing. The greatest of these pre-Shakespearean writers was undoubtedly Christopher Marlowe. Many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays were also performed between 1600 and 1611, including Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth and The Tempest.

In 1599 Shakespeare’s company moved to the newly-built Globe. It had a massive stage – 43 feet wide and 23 feet deep – and was intended purely as a theatre. It was burned down in 1613 but was immediately rebuilt.

Shakespeare was a member of one of the two leading companies, the Chamberlain’s Men, and in fact had bought a share in the company when it was formed in 1594. He was not, however, their only playwright, for they also performed plays by Ben Jonson, Marston, Dekker, Middleton and Fletcher.

In 1608 the next significant step in the development of theatre took place: James I and his wife, Anne of Denmark, were particularly fond of masques, the more elaborate the better. To further this enjoyment, in 1604 Prince Henry appointed Inigo Jones to his household and he was the first in England (he had first-hand experience of Italian theatre) to use a proscenium arch and perspective scenery in The Masque of Blackness in 1605. He also experimented with the use of scenery that could be changed, by using decorated shutters which ran in grooves across the stage.

A masque Costume for a Knight, designed by Inigo Jones

A masque Costume for a Knight, designed by Inigo Jones

| In fact, scenery began to dominate in subsequent masques and the text began to take second place, particularly since the court was willing to spend lavish amounts of money on these entertainments. Inevitably this eventually had an effect on theatre, leading to the complexities of modern scenery. The theatre was not totally dead during the Civil War and the Parliament. In fact, there was even some innovation. In 1656 the playwright Sir William Davenant presented the first English opera, The Siege of Rhodes, at Rutland House. Important though that was in terms of the development of music theatre, it was even more significant |

because it was the first time that scenery innovations for court masques were used in the theatre.

Two important things happened after the restoration of the monarchy. Charles II decided that only two people should have the right to produce plays within the City of Westminster. The second development was the increasing involvement of women in professional theatre. The content of plays changed too, reflecting the mood of the times. These “comedies of manners” reflected a society which prized wit, accepted adultery, and feared banishment from society.

|

|

|

The XVIII century was not a time of great playwrights. The most significant piece of theatre (in the widest sense) of the entire century was John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, a so-called ballad opera, which had a political as well as an artistic agenda.

The best of the century’s plays were written after 1750. Goldsmith began writing in 1768 with The Good-Natured Man, very much in the sentimental comedy tradition but with just a taste of the critical approach that was to come later in She Stoops to Conquer (1773), but was the reach its peak in the work of Sheridan with The Rivals (1775), The School for Scandal (1777) and The Critic (1779).

| Another form of theatre, which is unique to Britain, also began at this time: pantomime. John Rich was the first to introduce pantomime to the English stage and he himself played a dancing and mute Harlequin himself from 1717 – 1760 under the stage name of “Lun” at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Pantomimes were a great success, so much so that Lun/Rich was able to build another theatre in Covent Garden, just round the corner from Drury Lane. Both Drury Lane and Covent Garden were revamped in the nineties to seat in excess of 3000 people. |  Rich as Harlequin, c. 1720

Rich as Harlequin, c. 1720

|

In 1741 there was the start of the real flowering of the actor’s art. In the October of that year Garrick made his first appearance in Richard III in Goodman’s Fields. Garrick was not only an actor but a manager, running Drury Lane from 1747 to 1776, who approached the modern director in his control over what his actors did on-stage and who banned the practice of audience members sitting on the actual stage.

In the latter half of the century, two other still famous names came: the actor-manager John Philip Kemble and his sister Sarah Siddons.

At the turn of the century the scene was set for the development of melodrama. There are similarities between tragedy and melodrama: in both the hero or heroine is placed in a situation of grave danger which threatens to destroy them, but the differences are extremely significant: in tragedy the hero is of heroic stature (Macbeth of Scotland), whereas the hero or, more usually, heroine of melodrama is really just an ordinary person.

The domination of melodrama did not mean that the major genres of tragedy and comedy were forgotten. Keats attempted a tragedy, Otho the Great, Shelley made a number of excursions into playwriting, with “lyrical dramas”. It was Byron, however, who was the most committed to writing plays: Manfred, a dramatic poem in three acts; Marino Faliero, Doge of Venice, a historial tragedy in five acts, etc. Other poets who tried their hands at writing tragedy were Browning and Tennyson.

Comedy had a more successful century than tragedy, the comic masterpiece of the century is still played regularly today, by both amateur and professional companies – Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). The “golden age” of British farce, of course, was still to come with the work of writers like Ben Travers, but already the influence of French farce was being strongly felt. The best known name among the purveyors of these one-act farces was W.S. Gilbert.

Generally theatre and opera of all kinds were very much the province of the middle and upper classes: for the working class the entertainment of choice was the Music Hall, basically a variety show with emphasis on music, but, as the end of the century approached, this changed and large scale variety theatres began to be built by such as Oswald Stoll, Edward Moss and Richard Thornton.

Writers of the XX century – with one exception – gave up on the attempt to create a poetic tragedy. The one exception, of course, was T.S. Eliot, whose Murder in the Cathedral, The Family Reunion and The Cocktail Party are now generally considered to be in the province of literature rather than performance.

Before the Second World War comedy – sometimes light, sometimes brittle, sometimes farce – was the order of the day. Given the horrors of the first war and the desire never to have to face them again, it is not surprising that theatre tended towards the escapist.

|

|

|

After World War II began a veritable explosion of new theatre and theatrical ideas:

· politically committed theatre;

· theatre which was surreal and absurd;

· feminist theatre;

· dance drama;

· site-specific and environmental theatre.

And at the same time along came Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber with Jesus Christ Superstar which, together with the excitement generated a decade earlier by West Side Story, revolutionized our perception of what a musical could be. A little later Cats was to become the most popular musical ever, bringing dance to a prominence it had hitherto lacked in the theatre.

Since at least the time of Shakespeare, London has always been the centre of British theatre, and for centuries the regions more or less got the crumbs from the capital’s table. A significant date here is 1946, the year in which the Arts Council was founded. Its twin aims of fostering and funding the arts encouraged the growth of repertory theatre in the regions. Rep wasn’t a new thing, for small rep companies could be found all over the country even as early as the 1920s, but what was new was the spirit of experimentation which was the hallmark of the new breed of subsidised reps.

As for the National Companies, the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre opened in Stratford-on-Avon in 1879 and was burnt to the ground in 1926, a year after it had received the royal charter. The present building was opened in 1932.

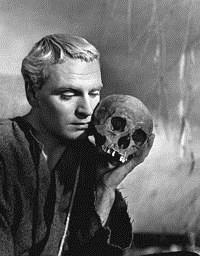

| In 1963 that he National Theatre Company was founded under Laurence Olivier and he put on his first performance (Hamlet) at the Old Vic. As a result of the success of the season, the architect Denys Lasdon was commissioned to design the building which is the National Theatre we know today. And so we come to the end of this history of a thousand years of British theatre. |  Laurence Olivier in Hamlet

Laurence Olivier in Hamlet

|

(from “Wikipedia”)

2. Read Text 2. Get ready to answer the questions and retell the text.

|

|

|