|

Word-meaning

|

|

|

|

§ 1. Referential Approach There are broadly speaking two schools to Meaning of thought in present-day linguistics representing the main lines of contemporary thinking on the problem: the referential approach, which seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and the things or concepts they denote, and the functional approach, which studies the functions of a word in speech and is less concerned with what meaning is than with how it works.

1 See ‘Introduction’, § 1.

1 See ‘Introduction’, § 1.

2 Sometimes the term semantics is used too, but in Soviet linguistics preference is given to semasiоlоgу as the word semantics is often used to designate one of the schools of modern idealistic philosophy and is also found as a synonym of meaning.

3 D. Bolinger. Getting the Words In. Lexicography in English, N. Y., 1973.

4 See, e. g., the discussion of various concepts of meaning in modern linguistics in: Л. С. Бархударов. Язык и перевод. М., 1975, с, 50 — 70.

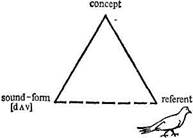

All major works on semantic theory have so far been based on referential concepts of meaning. The essential feature of this approach is that it distinguishes between the three components closely connected with meaning: the sound-form of the linguistic sign, the concept underlying this sound-form, and the actual referent, i. e. that part or that aspect of reality to which the linguistic sign refers. The best known referential model of meaning is the so-called “basic triangle” which, with some variations, underlies the semantic systems of all the adherents of this school of thought. In a simplified form the triangle may be represented as shown below:

As can be seen from the diagram the sound-form of the linguistic sign, e. g. [dAv], is connected with our concept of the bird which it denotes and through it with the referent, i. e. the actual bird. 1 The common feature of any referential approach is the implication that meaning is in some form or other connected with the referent.

Let us now examine the place of meaning in this model. It is easily observed that the sound-form of the word is not identical with its meaning, e. g. [dAv] is the sound-form used to denote a peal-grey bird. There is no inherent connection, however, between this particular sound-cluster and the meaning of the word dove. The connection is conventional and arbitrary. This can be easily proved by comparing the sound-forms of different languages conveying one and the same meaning, e. g. English [dAv], Russian [golub'], German [taube] and so on. It can also be proved by comparing almost identical sound-forms that possess different meaning in different languages. The sound-cluster [kot], e. g. in the English language means ‘a small, usually swinging bed for a child’, but in the Russian language essentially the same sound-cluster possesses the meaning ‘male cat’. -

1 As terminological confusion has caused much misunderstanding and often makes it difficult to grasp the semantic concept of different linguists we find it necessary to mention the most widespread terms used in modern linguistics to denote the three components described above:

1 As terminological confusion has caused much misunderstanding and often makes it difficult to grasp the semantic concept of different linguists we find it necessary to mention the most widespread terms used in modern linguistics to denote the three components described above:

|

|

|

sound-form — concept — referent

symbol — thought or reference — referent

sign — meaning — thing meant

sign — designatum — denotatum

For more convincing evidence of the conventional and arbitrary nature of the connection between sound-form and meaning all we have to do is to point to the homonyms. The word seal [si: l], e. g., means ‘a piece of wax, lead’, etc. stamped with a design; its homonym seal [si: l] possessing the same sound-form denotes ‘a sea animal’.

Besides, if meaning were inherently connected with the sound-form of a linguistic unit, it would follow that a change in sound-form would necessitate a change of meaning. We know, however, that even considerable changes in the sound-form of a word in the course of its historical development do not necessarily affect its meaning. The sound-form of the OE. word lufian [ luvian] has undergone great changes, and has been transformed into love [lАv], yet the meaning ‘hold dear, bear love’, etc. has remained essentially unchanged.

When we examine a word we see that its meaning though closely connected with the underlying concept or concepts is not identical with them. To begin with, concept is a category of human cognition. Concept is the thought of the object that singles out its essential features. Our concepts abstract and reflect the most common and typical features of the different objects and phenomena of the world. Being the result of abstraction and generalisation all “concepts are thus intrinsically almost the same for the whole of humanity in one and the same period of its historical development. The meanings of words however are different in different languages. That is to say, words expressing identical concepts may have different meanings and different semantic structures in different languages. The concept of ‘a building for human habitation’ is expressed in English by the word house, in Russian by the word дом, but the meaning of the English word is not identical with that of the Russian as house does not possess the meaning of ‘fixed residence of family or household’ which is one of the meanings of the Russian word дом; it is expressed by another English polysemantic word, namely home which possesses a number of other meanings not to be found in the Russian word дом.

The difference between meaning and concept can also be observed by comparing synonymous words and word-groups expressing essentially the same concepts but possessing linguistic meaning which is felt as different in each of the units under consideration, e. g. big, large; to, die, to pass away, to kick the bucket, to join the majority; child, baby, babe, infant.

The precise definition of the content of a concept comes within the sphere of logic but it can be easily observed that the word-meaning is not identical with it. For instance, the content of the concept six can be expressed by ‘three plus three’, ‘five plus one’, or ‘ten minus four’, etc. Obviously, the meaning of the word six cannot be identified with the meaning of these word-groups.

To distinguish meaning from the referent, i. e. from the thing denoted by the linguistic sign is of the utmost importance, and at first sight does not seem to present difficulties. To begin with, meaning is linguistic whereas the denoted object or the referent is beyond the scope of language. We can denote one and the same object by more than one word of a different meaning. For instance, in a speech situation an apple can be denoted

|

|

|

by the words apple, fruit, something, this, etc. as all of these words may have the same referent. Meaning cannot be equated with the actual properties of the referent, e. g. the meaning of the word water cannot be regarded as identical with its chemical formula H2O as water means essentially the same to all English speakers including those who have no idea of its chemical composition. Last but not least there are words that have distinct meaning but do not refer to any existing thing, e. g. angel or phoenix. Such words have meaning which is understood by the speaker-hearer, but the objects they denote do not exist.

Thus, meaning is not to be identified with any of the three points of the triangle.

| § 2. Meaning in the Referential Approach |

It should be pointed out that among the adherents of the referential approach there are some who hold that the meaning of a linguistic sign is the concept underlying it, and consequently they substitute meaning for concept in the basic triangle. Others identify meaning with the referent. They argue that unless we have a scientifically accurate knowledge of the referent we cannot give a scientifically accurate definition of the meaning of a word. According to them the English word salt, e. g., means ’sodium chloride (NaCl)’. But how are we to define precisely the meanings of such words as love or hate, etc.? We must admit that the actual extent of human knowledge makes it impossible to define word-meanings accurately. 1 It logically follows that any study of meanings in linguistics along these lines must be given up as impossible.

Here we have sought to show that meaning is closely connected but not identical with sound-form, concept or referent. Yet even those who accept this view disagree as to the nature of meaning. Some linguists regard meaning as the interrelation of the three points of the triangle within the framework of the given language, i. e. as the interrelation of the sound-form, concept and referent, but not as an objectively existing part of the linguistic sign. Others and among them some outstanding Soviet linguists, proceed from the basic assumption of the objectivity of language and meaning and understand the linguistic sign as a two-facet unit. They view meaning as “a certain reflection in our mind of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic sign — its so-called inner facet, whereas the sound-form functions as its outer facet. ” 2 The outer facet of the linguistic sign is indispensable to meaning and intercommunication. Meaning is to be found in all linguistic units and together with their sound-form constitutes the linguistic signs studied by linguistic science.

The criticism of the referential theories of meaning may be briefly summarised as follows:

1. Meaning, as understood in the referential approach, comprises the interrelation of linguistic signs with categories and phenomena outside the scope of language. As neither referents (i. e. actual things, phenomena,

1 See, e. g., L. Bloomfield. Language. N. Y., 1933, p. 139.

1 See, e. g., L. Bloomfield. Language. N. Y., 1933, p. 139.

2 А. И. Смирницкий. Значение слова. — Вопр. языкознания, 1955, № 2. See also С. И. Ожегов. Лексикология, лексикография, культура речи. М., 1974, с. 197.

etc. ) nor concepts belong to language, the analysis of meaning is confined either to the study of the interrelation of the linguistic sign and referent or that of the linguistic sign and concept, all of which, properly speaking, is not the object of linguistic study.

|

|

|

2. The great stumbling block in referential theories of meaning has always been that they operate with subjective and intangible mental processes. The results of semantic investigation therefore depend to a certain extent on “the feel of the language” and cannot be verified by another investigator analysing the same linguistic data. It follows that semasiology has to rely too much on linguistic intuition and unlike other fields of linguistic inquiry (e. g. phonetics, history of language) does not possess objective methods of investigation. Consequently it is argued, linguists should either give up the study of meaning and the attempts to define meaning altogether, or confine their efforts to the investigation of the function of linguistic signs in speech.

| § 3. Functional Approach to Meaning |

In recent years a new and entirely different approach to meaning known as the functional approach has begun to take shape in linguistics and especially in structural linguistics. The functional approach maintains that the meaning of a linguistic unit may be studied only through its relation to other linguistic-units and not through its relation to either concept or referent. In a very simplified form this view may be illustrated by the following: we know, for instance, that the meaning of the two words move and movement is different because they function in speech differently. Comparing the contexts in which we find these words we cannot fail to observe that they occupy different positions in relation to other words. (To) move, e. g., can be followed by a noun (move the chair), preceded by a pronoun (we move), etc. The position occupied by the word movement is different: it may be followed by a preposition (movement of smth), preceded by an adjective (slow movement), and so on. As the distribution l ofthe two words is different, we are entitled to the conclusion that not only do they belong to different classes of words, but that their meanings are different too.

The same is true of the different meanings of one and the same word. Analysing the function of a word in linguistic contexts and comparing these contexts, we conclude that; meanings are different (or the same) and this fact can be proved by an objective investigation of linguistic data. For example we can observe the difference of the meanings of the word take if we examine its functions in different linguistic contexts, take the tram (the taxi, the cab,, etc. ) as opposed to to take to somebody.

It follows that in the functional approach (1) semantic investigation is confined to the analysis of the difference or sameness of meaning; (2) meaning is understood essentially as the function of the use of linguistic units. As a matter of fact, this line of semantic investigation is the primary concern, implied or expressed, of all structural linguists.

1 By the term distribution we understand the position of a linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units.

1 By the term distribution we understand the position of a linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units.

| § 4. Relation between the Two Approaches |

When comparing the two approaches described above in terms of methods of linguistic analysis we see that the functional approach should not be considered an alternative, but rather a valuable complement to the referential theory. It is only natural that linguistic investigation must start by collecting an adequate number of samples of contexts. 1 On examination the meaning or meanings of linguistic units will emerge from the contexts themselves. Once this phase had been completed it seems but logical to pass on to the referential phase and try to formulate the meaning thus identified. There is absolutely no need to set the two approaches against each other; each handles its own side of the problem and neither is complete without the other.

|

|

|

TYPES OF MEANING

It is more or less universally recognised that word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up of various components the combination and the interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. These components are usually described as types of meaning. The two main types of meaning that are readily observed are the grammatical and the lexical meanings to be found in words and word-forms.

| § 5. Grammatical Meaning |

We notice, e. g., that word-forms, such as girls, winters, joys, tables, etc. though denoting widely different objects of reality have something in common. This common element is the grammatical meaning of plurality which can be found in all of them.

Thus grammatical meaning may be defined, as the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e. g., the tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked, thought, walked, etc. ) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s, boy’s, night’s, etc. ).

In a broad sense it may be argued that linguists who make a distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning are, in fact, making a distinction between the functional (linguistic) meaning which operates at various levels as the interrelation of various linguistic units and referential (conceptual) meaning as the interrelation of linguistic units and referents (or concepts).

In modern linguistic science it is commonly held that some elements of grammatical meaning can be identified by the position of the linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units, i. e. by its distribution. Word-forms speaks, reads, writes have one and the same grammatical meaning as they can all be found in identical distribution, e. g. only after the pronouns he, she, it and before adverbs like well, badly, to-day, etc.

1 It is of interest to note that the functional approach is sometimes described as contextual, as it is based on the analysis of various contexts. See, e. g., St. Ullmann. Semantics. Oxford, 1962, pp. 64-67.

1 It is of interest to note that the functional approach is sometimes described as contextual, as it is based on the analysis of various contexts. See, e. g., St. Ullmann. Semantics. Oxford, 1962, pp. 64-67.

It follows that a certain component of the meaning of a word is described when you identify it as a part of speech, since different parts of speech are distributionally different (cf. my work and I work). 1

| § 6. Lexical Meaning |

Comparing word-forms of one and the same word we observe that besides grammatical meaning, there is another component of meaning to be found in them. Unlike the grammatical meaning this component is identical in all the forms of the word. Thus, e. g. the word-forms go, goes, went, going, gone possess different grammatical meanings of tense, person and so on, but in each of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting the process of movement. This is the lexical meaning of the word which may be described as the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i. e. recurrent in all the forms of this word.

The difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of meaning is not to be sought in the difference of the concepts underlying the two types of meaning, but rather in the way they are conveyed. The concept of plurality, e. g., may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the world plurality; it may also be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of their lexical meaning, e. g. boys, girls, joys, etc. The concept of relation may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the word relation and also by any of the prepositions, e. g. in, on, behind, etc. (cf. the book is in/on, behind the table). “

It follows that by lexical meaning we designate the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions, while by grammatical meaning we designate the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class. Both the lexical and the grammatical meaning make up the word-meaning as neither can exist without the other. That can be also observed in the semantic analysis of correlated words in different languages. E. g. the Russian word сведения is not semantically identical with the English equivalent information because unlike the Russian сведения the English word does not possess the grammatical meaning of plurality which is part of the semantic structure of the Russian word.

| § 7. Parf-of-Speech Meaning |

It is usual to classify lexical items into major word-classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and minor word-classes (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, etc. ).

|

|

|

All members of a major word-class share a distinguishing semantic component which though very abstract may be viewed as the lexical component of part-of-speech meaning. For example, the meaning of ‘thingness’ or substantiality may be found in all the nouns e. g. table, love, sugar, though they possess different grammatical meanings of number, case, etc. It should be noted, however, that the grammatical aspect of the part-of-speech meanings is conveyed as a rule by a set of forms. If we describe the word as a noun we mean to say that it is bound to possess

1 For a more detailed discussion of the interrelation of the lexical and grammatical meaning in words see § 7 and also А. И. Смирницкий. Лексикология английского языка. М., 1956, с. 21 — 26.

1 For a more detailed discussion of the interrelation of the lexical and grammatical meaning in words see § 7 and also А. И. Смирницкий. Лексикология английского языка. М., 1956, с. 21 — 26.

a set of forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number (cf. table — tables), case (cf. boy, boy’s) and so on. A verb is understood to possess sets of forms expressing, e. g., tense meaning (worked — works), mood meaning (work! — (I) work), etc.

The part-of-speech meaning of the words that possess only one form, e. g. prepositions, some adverbs, etc., is observed only in their distribution (cf. to come in (here, there) and in (on, under) the table).

One of the levels at which grammatical meaning operates is that of minor word classes like articles, pronouns, etc.

Members of these word classes are generally listed in dictionaries just as other vocabulary items, that belong to major word-classes of lexical items proper (e. g. nouns, verbs, etc. ).

One criterion for distinguishing these grammatical items from lexical items is in terms of closed and open sets. Grammatical items form closed sets of units usually of small membership (e. g. the set of modern English pronouns, articles, etc. ). New items are practically never added.

Lexical items proper belong to open sets which have indeterminately large membership; new lexical items which are constantly coined to fulfil the needs of the speech community are added to these open sets.

The interrelation of the lexical and the grammatical meaning and the role played by each varies in different word-classes and even in different groups of words within one and the same class. In some parts of speech the prevailing component is the grammatical type of meaning. The lexical meaning of prepositions for example is, as a rule, relatively vague (independent of smb, one of the students, the roof of the house). The lexical meaning of some prepositions, however, may be comparatively distinct (cf. in/on, under the table). In verbs the lexical meaning usually comes to the fore although in some of them, the verb to be, e. g., the grammatical meaning of a linking element prevails (cf. he works as a teacher and he is a teacher).

| § 8. Denotational and Connotational Meaning |

Proceeding with the semantic analysis we observe that lexical meaning is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including denotational and connotational components.

As was mentioned above one of the functions of words is to denote things, concepts and so on. Users of a language cannot have any knowledge or thought of the objects or phenomena of the real world around them unless this knowledge is ultimately embodied in words which have essentially the same meaning for all speakers of that language. This is the denotational meaning, i. e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. There is no doubt that a physicist knows more about the atom than a singer does, or that an arctic explorer possesses a much deeper knowledge of what arctic ice is like than a man who has never been in the North. Nevertheless they use the words atom, Arctic, etc. and understand each other.

The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i. e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.

§ 9. Emotive Charge

Words contain an element of emotive evaluation as part of the connotational meaning; e. g. a hovel denotes ‘a small house or cottage’ and besides implies that it is a miserable dwelling place, dirty, in bad repair and in general unpleasant to live in. When examining synonyms large, big, tremendous and like, love, worship or words such as girl, girlie; dear, dearie we cannot fail to observe the difference in the emotive charge of the members of these sets. The emotive charge of the words tremendous, worship and girlie is heavier than that of the words large, like and girl. This does not depend on the “feeling” of the individual speaker but is true for all speakers of English. The emotive charge varies in different word-classes. In some of them, in interjections, e. g., the emotive element prevails, whereas in conjunctions the emotive charge is as a rule practically non-existent.

The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning. It should not be confused with emotive implications that the words may acquire in speech. The emotive implication of the word is to a great extent subjective as it greatly depends of the personal experience of the speaker, the mental imagery the word evokes in him. Words seemingly devoid of any emotional element may possess in the case of individual speakers strong emotive implications as may be illustrated, e. g. by the word hospital. What is thought and felt when the word hospital is used will be different in the case of an architect who built it, the invalid staying there after an operation, or the man living across the road.

| § 10. Sfylistic Reference |

Words differ not only in their emotive charge but also in their stylistic reference. Stylistically words can be roughly subdivided into literary, neutral and colloquial layers. 1

The greater part of the literаrу layer of Modern English vocabulary are words of general use, possessing no specific stylistic reference and known as neutral words. Against the background of neutral words we can distinguish two major subgroups — standard colloquial words and literary or bookish words. This may be best illustrated by comparing words almost identical in their denotational meaning, e. g., ‘ parent — father — dad’. In comparison with the word father which is stylistically neutral, dad stands out as colloquial and parent is felt as bookish. The stylistic reference of standard colloquial words is clearly observed when we compare them with their neutral synonyms, e. g. chum — friend, rot — nonsense, etc. This is also true of literary or bookish words, such as, e. g., to presume (cf. to suppose), to anticipate (cf. to expect) and others.

Literary (bookish) words are not stylistically homogeneous. Besides general-literary (bookish) words, e. g. harmony, calamity, alacrity, etc., we may single out various specific subgroups, namely: 1) terms or

1 See the stylistic classification of the English vocabulary in: I. R. Galperin. Stylistics. M., 1971, pp. 62-118.

1 See the stylistic classification of the English vocabulary in: I. R. Galperin. Stylistics. M., 1971, pp. 62-118.

scientific words such as, e g., renaissance, genocide, teletype, etc.; 2) poetic words and archaisms such as, e. g., whilome — ‘formerly’, aught — ‘anything’, ere — ‘before’, albeit — ‘although’, fare — ‘walk’, etc., tarry — ‘remain’, nay — ‘no’; 3) barbarisms and foreign words, such as, e. g., bon mot — ‘a clever or witty saying’, apropos, faux pas, bouquet, etc. The colloquial words may be subdivided into:

1) Common colloquial words.

2) Slang, i. e. words which are often regarded as a violation of the norms of Standard English, e. g. governor for ‘father’, missus for ‘wife’, a gag for ‘a joke’, dotty for ‘insane’.

3) Professionalisms, i. e. words used in narrow groups bound by the same occupation, such as, e. g., lab for ‘laboratory’, hypo for ‘hypodermic syringe’, a buster for ‘a bomb’, etc.

4) Jargonisms, i. e. words marked by their use within a particular social group and bearing a secret and cryptic character, e. g. a sucker — ‘a person who is easily deceived’, a squiffer — ‘a concertina’.

5) Vulgarisms, i. e. coarse words that are not generally used in public, e. g. bloody, hell, damn, shut up, etc.

6) Dialectical words, e. g. lass, kirk, etc.

7) Colloquial coinages, e. g. newspaperdom, allrightnik, etc.

| § 11. Emotive Charge and Stylistic Reference |

Stylistic reference and emotive charge of words are closely connected and to a certain degree interdependent. 1 As a rule stylistically coloured words, i. e. words belonging to all stylistic layers except the neutral style are observed to possess a considerable emotive charge. That can be proved by comparing stylistically labelled words with their neutral synonyms. The colloquial words daddy, mammy are more emotional than the neutral father, mother; the slang words mum, bob are undoubtedly more expressive than their neutral counterparts silent, shilling, the poetic yon and steed carry a noticeably heavier emotive charge than their neutral synonyms there and horse. Words of neutral style, however, may also differ in the degree of emotive charge. We see, e. g., that the words large, big, tremendous, though equally neutral as to their stylistic reference are not identical as far as their emotive charge is concerned.

| § 12. Summary and Conclusions |

1. In the present book word-meaning is viewed as closely connected but not identical with either the sound-form of the word or with its referent.

Proceeding from the basic assumption of the objectivity of language and from the understanding of linguistic units as two-facet entities we regard meaning as the inner facet of the word, inseparable from its outer facet which is indispensable to the existence of meaning and to intercommunication.

1 It should be pointed out that the interdependence and interrelation of the emotive and stylistic component of meaning is one of the debatable problems in semasiology. Some linguists go so far as to claim that the stylistic reference of the word lies outside the scope of its meaning. (See, e. g., В. А. Звягинцев. Семасиология. M, 1957, с. 167 — 185).

1 It should be pointed out that the interdependence and interrelation of the emotive and stylistic component of meaning is one of the debatable problems in semasiology. Some linguists go so far as to claim that the stylistic reference of the word lies outside the scope of its meaning. (See, e. g., В. А. Звягинцев. Семасиология. M, 1957, с. 167 — 185).

2. The two main types of word-meaning are the grammatical and the lexical meanings found in all words. The interrelation of these two types of meaning may be different in different groups of words.

3. Lexical meaning is viewed as possessing denotational and connotational components.

The denotational component is actually what makes communication possible. The connotational component comprises the stylistic reference and the emotive charge proper to the word as a linguistic unit in the given language system. The subjective emotive implications acquired by words in speech lie outside the semantic structure of words as they may vary from speaker to speaker but are not proper to words as units of language.

WORD-MEANING AND MEANING IN MORPHEMES

In modern linguistics it is more or less universally recognised that the smallest two-facet language unit possessing both sound-form and meaning is the morpheme. Yet, whereas the phono-morphological structure of language has been subjected to a thorough linguistic analysis, the problem of types of meaning and semantic peculiarities of morphemes has not been properly investigated. A few points of interest, however, may be mentioned in connection with some recent observations in “this field.

| § 13. Lexical Meaning |

It is generally assumed that one of the semantic features of some morphemes which distinguishes them from words is that they do not possess grammatical meaning. Comparing the word man, e. g., and the morpheme man-(in manful, manly, etc. ) we see that we cannot find in this morpheme the grammatical meaning of case and number observed in the word man. Morphemes are consequently regarded as devoid of grammatical meaning.

Many English words consist of a single root-morpheme, so when we say that most morphemes possess lexical meaning we imply mainly the root-morphemes in such words. It may be easily observed that the lexical meaning of the word boy and the lexical meaning of the root-morpheme boy — in such words as boyhood, boyish and others is very much the same.

Just as in words lexical meaning in morphemes may also be analysed into denotational and connotational components. The connotational component of meaning may be found not only in root-morphemes but in affixational morphemes as well. Endearing and diminutive suffixes, e. g. - ette (kitchenette), -ie(y) (dearie, girlie), -ling (duckling), clearly bear a heavy emotive charge. Comparing the derivational morphemes with the same denotational meaning we see that they sometimes differ in connotation only. The morphemes, e. g. -ly, -like, -ish, have the denotational meaning of similarity in the words womanly, womanlike, womanish, the connotational component, however, differs and ranges from the positive evaluation in -ly (womanly) to the derogatory in -ish (womanish): 1 Stylistic reference may also be found in morphemes of differ-

1 Compare the Russian equivalents: женственный — женский — женоподобный, бабий.

1 Compare the Russian equivalents: женственный — женский — женоподобный, бабий.

ent types. The stylistic value of such derivational morphemes as, e. g. -ine (chlorine), -oid (rhomboid), -escence (effervescence) is clearly perceived to be bookish or scientific.

| § 14. Functional (Parf-of-Speech) Meaning |

The lexical meaning of the affixal morphemes is, as a rule, of a more generalising character. The suffix -er, e. g. carries the meaning ‘the agent, the doer of the action’, the suffix -less denotes lack or absence of something. It should also be noted that the root-morphemes do not “possess the part-of-speech meaning (cf. manly, manliness, to man); in derivational morphemes the lexical and the part-of-speech meaning may be so blended as to be almost inseparable. In the derivational morphemes -er and -less discussed above the lexical meaning is just as clearly perceived as their part-of-speech meaning. In some morphemes, however, for instance -ment or -ous (as in movement or laborious), it is the part-of-speech meaning that prevails, the lexical meaning is but vaguely felt.

In some cases the functional meaning predominates. The morpheme -ice in the word justice, e. g., seems to serve principally to transfer the part-of-speech meaning of the morpheme just — into another class and namely that of noun. It follows that some morphemes possess only the functional meaning, i. e. they are the carriers of part-of-speech meaning.

| § 15. Differential Meaning |

Besides the types of meaning proper both to words and morphemes the latter may possess specific meanings of their own, namely the differential and the distributional meanings. Differential meaning is the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. In words consisting of two or more morphemes, one of the constituent morphemes always has differential meaning. In such words as, e. g., bookshelf, the morpheme -shelf serves to distinguish the word from other words containing the morpheme book-, e. g. from bookcase, book-counter and so on. In other compound words, e. g. notebook, the morpheme note- will be seen to possess the differential meaning which distinguishes notebook from exercisebook, copybook, etc. It should be clearly understood that denotational and differential meanings are not mutually exclusive. Naturally the morpheme -shelf in bookshelf possesses denotational meaning which is the dominant component of meaning. There are cases, however, when it is difficult or even impossible to assign any denotational meaning to the morpheme, e. g. cran- in cranberry, yet it clearly bears a relationship to the meaning of the word as a whole through the differential component (cf. cranberry and blackberry, gooseberry) which in this particular case comes to the fore. One of the disputable points of morphological analysis is whether such words as deceive, receive, perceive consist of two component morphemes. 1 If we assume, however, that the morpheme -ceive may be singled out it follows that the meaning of the morphemes re-, per, de- is exclusively differential, as, at least synchronically, there is no denotational meaning proper to them.

1 See ‘Word-Structure’, § 2, p. 90. 24

1 See ‘Word-Structure’, § 2, p. 90. 24

| § 16. Distributional Meaning |

Distributional meaning is the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. It is found in all words containing more than one morpheme. The word singer, e. g., is composed of two morphemes sing- and -er both of which possess the denotational meaning and namely ‘to make musical sounds’ (sing-) and ‘the doer of the action’ (-er). There is one more element of meaning, however, that enables us to understand the word and that is the pattern of arrangement of the component morphemes. A different arrangement of the same morphemes, e. g. *ersing, would make the word meaningless. Compare also boyishness and *nessishboy in which a different pattern of arrangement of the three morphemes boy-ish-ness turns it into a meaningless string of sounds. 1

WORD-MEANING AND MOTIVATION

From what was said about the distributional meaning in morphemes it follows that there are cases when we can observe a direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning. This relationship between morphemic structure and meaning is termed morphological motivation.

| § 17. Morphological Motivation |

The main criterion in morphological motivation is the relationship between morphemes. Hence all one-morpheme words, e. g. sing, tell, eat, are by definition non-motivated. In words composed of more than one morpheme the carrier of the word-meaning is the combined meaning of the component morphemes and the meaning of the structural pattern of the word. This can be illustrated by the semantic analysis of different words composed of phonemically identical morphemes with identical lexical meaning. The words finger-ring and ring-finger, e. g., contain two morphemes, the combined lexical meaning of which is the same; the difference in the meaning of these words can be accounted for by the difference in the arrangement of the component morphemes.

If we can observe a direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning, we say that this word is motivated. Consequently words such as singer, rewrite, eatable, etc., are described as motivated. If the connection between the structure of the lexical unit and its meaning is completely arbitrary and conventional, we speak of non-motivated or idiomatic words, e. g. matter, repeat.

It should be noted in passing that morphological motivation is “relative”, i. e. the degree of motivation may be different. Between the extremes of complete motivation and lack of motivation, there exist various grades of partial motivation. The word endless, e. g., is completely motivated as both the lexical meaning of the component morphemes and the meaning of the pattern is perfectly transparent. The word cranberry is

1 А. И. Смирницкий. Лексикология английского языка. М., 1956, с, 18 — 20.

1 А. И. Смирницкий. Лексикология английского языка. М., 1956, с, 18 — 20.

only partially motivated because of the absence of the lexical meaning in the morpheme cran-.

One more point should be noted in connection with the problem in question. A synchronic approach to morphological motivation presupposes historical changeability of structural patterns and the ensuing degree of motivation. Some English place-names may serve as an illustration. Such place-names as Newtowns and Wildwoods are lexically and structurally motivated and may be easily analysed into component morphemes. Other place-names, e. g. Essex, Norfolk, Sutton, are non-motivated. To the average English speaker these names are non-analysable lexical units like sing or tell. However, upon examination the student of language history will perceive their components to be East+Saxon, North+Folk and South+Town which shows that in earlier days they. were just as completely motivated as Newtowns or Wildwoods are in Modern English.

| § 18. Phonetical Motivation |

Motivation is usually thought of as proceeding from form or structure to meaning. Morphological motivation as discussed above implies a direct connection between the morphological structure of the word and its meaning. Some linguists, however, argue that words can be motivated in more than one way and suggest another type of motivation which may be described as a direct connection between the phonetical structure of the word and its meaning. It is argued that speech sounds may suggest spatial and visual dimensions, shape, size, etc. Experiments carried out by a group of linguists showed that back open vowels are suggestive of big size, heavy weight, dark colour, etc. The experiments were repeated many times and the results were always the same. Native speakers of English were asked to listen to pairs of antonyms from an unfamiliar (or non-existent) language unrelated to English, e. g. ching — chung and then to try to find the English equivalents, e. g. light — heavy, (big — small, etc. ), which foreign word translates which English word. About 90 per cent of English speakers felt that ching is the equivalent of the English light (small) and chung of its antonym heavy (large).

It is also pointed out that this type of phonetical motivation may be observed in the phonemic structure of some newly coined words. For example, the small transmitter that specialises in high frequencies is called ‘a tweeter’, the transmitter for low frequences ‘a woofer’.

Another type of phonetical motivation is represented by such words as swish, sizzle, boom, splash, etc. These words may be defined as phonetically motivated because the soundclusters [swi∫, sizl, bum, splæ ∫ ] are a direct imitation of the sounds these words denote. It is also suggested that sounds themselves may be emotionally expressive which accounts for the phonetical motivation in certain words. Initial [f] and [p], e. g., are felt as expressing scorn, contempt, disapproval or disgust which can be illustrated by the words pooh! fie! fiddle-sticks, flim-flam and the like. The sound-cluster [iŋ ] is imitative of sound or swift movement as can be seen in words ring, sing, swing, fling, etc. Thus, phonetically such words may be considered motivated.

This hypothesis seems to require verification. This of course is not to

deny that there are some words which involve phonetical symbolism: these are the onomatopoeic, imitative or echoic words such as the English cuckoo, splash and whisper: And even these are not completely motivated but seem to be conventional to quite a large extent (cf. кукареку and cock-a-doodle-doo). In any case words like these constitute only a small and untypical minority in the language. As to symbolic value of certain sounds, this too is disproved by the fact that identical sounds and sound-clusters may be found in words of widely different meaning, e. g. initial [p] and [f], are found in words expressing contempt and disapproval (fie, pooh) and also in such words as ploughs fine, and others. The sound-cluster [in] which is supposed to be imitative of sound or swift movement (ring, swing) is also observed in semantically different words, e. g. thing, king, and others.

| § 19. Semantic Motivation |

The term motivation is also used by a number of linguists to denote the relationship between the central and the coexisting meaning or meanings of a word which are understood as a metaphorical extension of the central meaning. Metaphorical extension may be viewed as generalisation of the denotational meaning of a word permitting it to include new referents which are in some way like the original class of referents. Similarity of various aspects and/or functions of different classes of referents may account for the semantic motivation of a number of minor meanings. For example, a woman who has given birth is called a mother; by extension, any act that gives birth is associated with being a mother, e. g. in Necessity is the mother of invention. The same principle can be observed in other meanings: a mother looks after a child, so that we can say She became a mother to her orphan nephew, or Romulus and Remus were supposedly mothered by a wolf. Cf. also mother country, a mother’s mark (=a birthmark), mother tongue, etc. Such metaphoric extension may be observed in the so-called trite metaphors, such as burn with anger, break smb’s heart, jump at a chance, etc.

If metaphorical extension is observed in the relationship of the central and a minor word meaning it is often observed in the relationship between its synonymic or antonymic meanings. Thus, a few years ago the phrases a meeting at the summit, a summit meeting appeared in the newspapers.

Cartoonists portrayed the participants of such summit meetings sitting on mountain tops. Now when lesser diplomats confer the talks are called foothill meetings. In this way both summit and its antonym foothill undergo the process of metaphorical extension.

| § 20. Summary and Conclusions |

1. Lexical meaning with its denotational and connotational components may be found in morphemes of different types. The denotational meaning in affixal morphemes may be rather vague and abstract, the lexical meaning and the part-of-speech meaning tending to blend.

2. It is suggested that in addition to lexical meaning morphemes may contain specific types of meaning: differential, functional and distributional.

3. Differential meaning in morphemes is the semantic component

which serves to distinguish one word from other words of similar morphemic structure. Differential and denotational meanings are not mutually exclusive.

4. Functional meaning is the semantic component that serves primarily to refer the word to a certain part of speech.

5. Distributional meaning is the meaning of the pattern of the arrangement of the morphemes making up the word. Distributional meaning is to be found in all words composed of more than one morpheme. It may be the dominant semantic component in words containing morphemes deprived of denotational meaning.

6. Morphological motivation implies a direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes, the pattern of their arrangement and the meaning of the word. The degree of morphological motivation may be different varying from the extreme of complete motivation to lack of motivation.

7. Phonetical motivation implies a direct connection between the phonetic structure of the word and its meaning. Phonetical motivation is not universally recognised in modern linguistic science.

8. Semantic motivation implies a direct connection between the central and marginal meanings of the word. This connection may be regarded as a metaphoric extension of the central meaning based on the similarity of different classes of referents denoted by the word.

CHANGE Of MEANING

Word-meaning is liable to change in the course of the historical development of language. Changes of lexical meaning may be illustrated by a diachronic semantic analysis of many commonly used English words. The word fond (OE. fond) used to mean ‘foolish’, ‘foolishly credulous’; glad (OE, glaed) had the meaning of ‘bright’, ’shining’ and so on.

Change of meaning has been thoroughly studied and as a matter of fact monopolised the attention of all semanticists whose work up to the early 1930’s was centered almost exclusively on the description and classification of various changes of meaning. Abundant language data can be found in almost all the books dealing with semantics. Here we shall confine the discussion to a brief outline of the problem as it is viewed in modern linguistic science.

To avoid the ensuing confusion of terms and concepts it is necessary to discriminate between the causes of semantic change, the results and the nature of the process of change of meaning. 1 These are three closely bound up, but essentially different aspects of one and the same problem.

Discussing the causes of semantic change we concentrate on the factors bringing about -this change and attempt to find out why the word changed its meaning. Analysing the nature of semantic change we seek

i See St. Ullmann. The Principles of Semantics. Chapter 8, Oxford, 1963. 28

i See St. Ullmann. The Principles of Semantics. Chapter 8, Oxford, 1963. 28

to clarify the process of this change and describe how various changes of meaning were brought about. Our aim in investigating the results of semantic change is to find out what was changed, i. e. we compare the resultant and the original meanings and describe the difference between them mainly in terms of the changes of the denotational components.

| § 21. Causes of Semantic Change |

The factors accounting for semantic changes may be roughly subdivided into two groups: a) extra-linguistic and b) linguistic causes.

By extra-linguistic causes we mean various changes in the life of the speech community, changes in economic and social structure, changes in ideas, scientific concepts, way of life and other spheres of human activities as reflected in word meanings. Although objects, institutions, concepts, etc. change in the course of time in many cases the soundform of the words which denote them is retained but the meaning of the words is changed. The word car, e. g., ultimately goes back to Latin carrus which meant ‘a four-wheeled wagon’ (ME. carre) but now that other means of transport are used it denotes ‘a motor-car’, ‘a railway carriage’ (in the USA), ‘that portion of an airship, or balloon which is intended to carry personnel, cargo or equipment’.

Some changes of meaning are due to what may be described as purely linguistic causes, i. e. factors acting within the language system. The commonest form which this influence takes is the so-called ellipsis. In a phrase made up of two words one of these is omitted and its meaning is transferred to its partner. The verb to starve, e. g., in Old English (OE. steorfan) had the meaning ‘to die’ and was habitually used in collocation with the word hunger (ME. sterven of hunger). Already in the 16th century the verb itself acquired the meaning ‘to die of hunger’. Similar semantic changes may be observed in Modern English when the meaning of one word is transferred to another because they habitually occur together in speech.

Another linguistic cause is discrimination of synonyms which can be illustrated by the semantic development of a number of words. The word land, e. g., in Old English (OE. land) meant both ’solid part of earth’s surface’ and ‘the territory of a nation’. When in the Middle English period the word country (OFr. contree) was borrowed as its synonym, the meaning of the word land was somewhat altered and ‘the territory of a nation’ came to be denoted mainly by the borrowed word country.

Some semantic changes may be accounted for by the influence of a peculiar factor usually referred to as linguistic analogy. It was found out, e. g., that if one of the members of a synonymic set acquires a new meaning other members of this set change their meanings too. It was observed, e. g., that all English adverbs which acquired the meaning ‘rapidly’ (in a certain period of time — before 1300) always develop the meaning ‘immediately’, similarly verbs synonymous with catch, e. g. grasp, get, etc., by semantic extension acquired another meaning — ‘to understand’. 1

1 See ‘Semasiology’, § 19, p. 27,

1 See ‘Semasiology’, § 19, p. 27,

| § 22. Nature of Semantic Change |

Generally speaking, a necessary condition of any semantic change, no matter what its cause, is some connection, some association between the old meaning and the new. There are two kinds of association involved as a rule in various semantic changes namely: a) similarity of meanings, and b) contiguity of meanings.

Similarity of meanings or metaphor may be described as a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some way resembles the other. The word hand, e. g., acquired in the 16th century the meaning of ‘a pointer of a clock of a watch’ because of the similarity of one of the functions performed by the hand (to point at something) and the function of the clockpointer. Since metaphor is based on the perception of similarities it is only natural that when an analogy is obvious, it should give rise to a metaphoric meaning. This can be observed in the wide currency of metaphoric meanings of words denoting parts of the human body in various languages (cf. ‘the leg of the table’, ‘the foot of the hill’, etc. ). Sometimes it is similarity of form, outline, etc. that underlies the metaphor. The words warm and cold began to denote certain qualities of human voices because of some kind of similarity between these qualities and warm and cold temperature. It is also usual to perceive similarity between colours and emotions.

It has also been observed that in many speech communities colour terms, e. g. the words black and white, have metaphoric meanings in addition to the literal denotation of colours.

Contiguity of meanings or metonymy may be described as the semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it.

, This can be perhaps best illustrated by the use of the word tongue — ‘the organ of speech’ in the meaning of ‘language’ (as in mother tongue; cf. also L. lingua, Russ. язык). The word bench acquired the meaning ‘judges, magistrates’ because it was on the bench that the judges used to sit in law courts, similarly the House acquired the meaning of ‘members of the House’ (Parliament).

It is generally held that metaphor plays a more important role in the change of meaning than metonymy. A more detailed analysis would show that there are some semantic changes that fit into more than the two groups discussed above. A change of meaning, e. g., may be brought about by the association between the sound-forms of two words. The word boon, e. g. ”, originally meant ‘prayer, petition’, ‘request’, but then came to denote ‘a thing prayed or asked for’. Its current meaning is ‘a blessing, an advantage, a thing to be thanked for. ’ The change of meaning was probably due to the similarity to the sound-form of the adjective boon (an Anglicised form of French bon denoting ‘good, nice’).

Within metaphoric and metonymic changes we can single out various subgroups. Here, however, we shall confine ourselves to a very general outline of the main types of semantic association as discussed above. A more detailed analysis of the changes of meaning and the nature of such changes belongs in the diachronic or historical lexicology and lies outside the scope of the present textbook.

| § 23. Results of Semantic Change |

Results of semantic change can be generally observed in the changes of the denotational meaning of the word (restriction and extension of meaning) or in the alteration of its connotational component (amelioration and deterioration of meaning).

Changes in the denotational meaning may result in the restriction of the types or range of referents denoted by the word. This may be illustrated by the semantic development of the word hound (OE. hund) which used to denote ‘a dog of any breed’ but now denotes only ‘a dog used in the chase’. This is also the case with the word fowl (OE. fuzol, fuzel) which in old English denoted ‘any bird’, but in Modern English denotes ‘a domestic hen or cock’. This is generally described as “restriction of meaning” and if the word with the new meaning comes to be used in the specialised vocabulary of some limited group within the speech community it is usual to speak of specialisation of meaning. For example, we can observe restriction and specialisation of meaning in the case of the verb to glide (OE. glidan) which had the meaning ‘to move gently and smoothly’ and has now acquired a restricted and specialised meaning ‘to fly with no engine’ (cf. a glider).

Changes in the denotational meaning may also result in the application of the word to a wider variety of referents. This is commonly described as extension of meaning and may be illustrated by the word target which originally meant ‘a small round shield’ (a diminutive of targe, сf. ON. targa) but now means ‘anything that is fired at’ and also figuratively ‘any result aimed at’.

If the word with the extended meaning passes from the specialised vocabulary into common use, we describe the result of the semantic change as the generalisation of meaning. The word camp, e. g., which originally was used only as a military term and meant ‘the place where troops are lodged in tents’ (cf. L. campus — ‘exercising ground for the army) extended and generalised its meaning and now denotes ‘temporary quarters’ (of travellers, nomads, etc. ).

As can be seen from the examples discussed above it is mainly the denotational component of the lexical meaning that is affected while the connotational component remains unaltered. There are other cases, however, when the changes in the connotational meaning come to the fore. These changes, as a rule accompanied by a change in the denotational’ component, may be subdivided into two main groups: a) pejorative development or the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emoti

|

|

|