|

The church schism

|

|

|

|

The first crisis which posed such challenges was the schism of the mid‑ 17th century. Many viewed the Time of Troubles as God’s punishment for the church’s sins, and so a movement had grown up to correct and coordinate the conduct of the liturgy and to purify the morals of clergy and believers. Like their counterparts in several European countries, both Catholic and Protestant, they aimed to tidy up church services and to purge religious life of folk practices. The Zealots of Piety, as they were known, objected to drinking, dancing, bear‑ baiting, and to the profane and sometimes obscene performances of the strolling players (skomorokhi ). They became influential at the court of Tsar Aleksei (r. 1645–76), and one of their number, Metropolitan Nikon of Novgorod, was elected Patriarch in 1652.

Nikon’s reforming motives differed, however, from those of his colleagues. Whereas they were concerned entirely with the Muscovite church, he had a broader agenda. Encouraged by the recent annexation of the Ukrainian Hetmanate, he aimed to turn the Moscow Patriarchate into an ecumenical patriarchate, an Eastern Rome, dominant over both the Tsar and the other Orthodox churches. To render the Muscovite church worthy of its grandiose mission, however, he wanted to be sure that its practices accorded with the rites of the ancient ecumenical church. His contact with Greek and Ukrainian churchmen had alerted him to discrepancies between their texts and rituals and those of Muscovy. Assuming that the Muscovite versions were recent errors, he assembled variant texts and scholars, including some from Greece, Ukraine, and even Italy, to make corrections.

As a result of their studies, he ordered a slight amendment in the spelling of ‘Jesus’ and instructed congregations to make a number of liturgical changes, including reciting three Alleluias after the Psalms instead of two and making the sign of the cross with three fingers instead of two. None of these changes had any doctrinal significance, but for largely illiterate congregations, every detail of the liturgy was sacrosanct. Moreover, Nikon violated custom by imposing the changes without convening a church council to endorse them.

Tsar Aleksei supported him. His motives, however, were different, imperial rather than ecumenical. He wanted the church’s practices reformed so that it could support the state in spreading its authority in the empire’s new lands. He required a supportive church, not a dominant one. Besides, he increasingly found Nikon’s supercilious behaviour repugnant and gradually cooled towards him. In 1658, offended by Aleksei’s aloofness, Nikon dramatically doffed his patriarchal robes in the middle of divine service and put on the simple habit of a monk. Aleksei accepted his resignation, but continued to support his reforms. Anxious to obtain endorsement from Constantinople, he invited Greek prelates to the church council of 1666–7. They were delighted to enforce Greek norms and invalidate the practices of the Russian church since it had broken with Constantinople in the 15th century. The council not only confirmed the reforms but pronounced anathema on those who rejected them as heretics and schismatics.

|

|

|

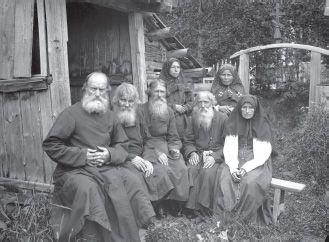

Opposition to the reforms came from those who objected to what seemed to them alien violations of long‑ consecrated Russian practice. ‘If we are schismatics, ’ they argued, ‘then the holy fathers, Tsars and Patriarchs were also schismatics. ’ Their protestations resonated with all those who opposed the church’s increasing institutionalization, the imposition from above of stereotyped liturgical forms, and the extirpation of ‘pagan’ practices. The Old Belief, as this opposition came to be called, thus had widespread support from both elites and masses. It provided a rallying point for all who objected to a more impersonal, centralized, and bureaucratic style of government, to Polonized Baroque architecture, or to the adoption of Western clothing and the import of Western books.

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of the Old Belief. It has survived to the present day, and indeed at times flourished, in spite of intermittent official persecution. It retained the vision which had enabled Muscovy to survive the Tatar overlordship, expand, and then come through the Time of Troubles – a vision of a world of local communities united by personal reverence of the Tsar, by the one true faith, and by obedience to pravda. Old Believers rejected a Latinate faith enforced by official decree and subservient priests. They became bearers of the old Muscovite messianic national myth in opposition to the new Russian imperial state, which the more radical among them regarded as the work of the Antichrist. The idea of Russia as the ‘Third Rome’, the ‘new Israel’, with its own ‘chosen people’, remained as an evocative substratum in Russian culture, always ready to re‑ emerge in one form or another.

|

|

|