|

1. The Caves Monastery, Kiev. Mongol overlordship

|

|

|

|

1. The Caves Monastery, Kiev

Iaroslav did his best to ensure strong collective leadership by regularizing the succession to the princely thrones, not in direct succession from father to son, but passing through the younger brothers according to seniority. This was to establish the principle that the realm was a kind of federation belonging to the princely family as a whole, while also removing the grounds for feuds within that family. The oldest living brother was to supervise the whole arrangement.

Collective rule was honoured in principle, but proved too difficult to manage in practice. After Iaroslav’s death, his brothers and cousins periodically fought each other over the inheritance, yet at times they had to curtail their feuds to face common threats from the nomadic horsemen of the steppe. During the especially alarming raids of the Kipchaks (or Polovtsy) in the 1090s, the princes met and renewed their dynastic agreement. It was successful in coping with the immediate danger, and gave Kievan Rus another generation of peace, but it did not prove durable.

In 1113, the citizens of Kiev invited Vladimir of Pereiaslavl, the most successful commander against the Kipchaks, to rule over them as Great Prince. After his victories, he received from Byzantium a fur‑ lined crown, the ‘Monomakh crown’, as a symbol of his God‑ given authority. He was a thoughtful and pious but also practical ruler, who believed in taking personal responsibility for all the major burdens of princely authority: war, the dynasty and its household, justice, charity and patronage, and the observance of pravda. He outlined his precepts in a written Exhortation (Pouchenie ) to his sons, urging them to rule not only through military means, but also through ‘repentance, tears, and almsgiving’. This combination of physical power with Christian morality continued to be an ideal for the rulers of Rus/Russia.

After Vladimir’s death, the fragmentation of Kievan Rus resumed. This happened partly because it was growing in size and prosperity. Trade was bringing economic activity to new areas, especially to the north and east, where there was abundant timber, furs and fish, and tree cover offered better protection against steppe raiders. New towns were founded and junior princes used them as bases for securing their own authority; in particular Vladimir, Suzdal, and Rostov became wealthy commercial centres, though as yet not serious rivals of Kiev and Novgorod. New churches were built and new bishoprics created under the aegis of the Kiev Metropolitan. At the same time, the princes’ feuding over land and succession rights repeatedly undermined these promising developments.

Mongol overlordship

In the early 13th century another, much more serious, danger emerged. Under the Mongol tribe, a new kind of steppe federation was being created, with its centre between Lake Baikal and the Great Wall of China. It created large, extremely mobile, and proficient cavalry armies, which conquered China under Chingis Khan. They then moved westwards, integrating the scattered nomadic tribes of Central Eurasia, among them the Kipchaks. Here the Rus princes’ disunity proved fatal. When the army of Batu, Chingis Khan’s grandson, approached Riazan in 1237, the princes were engaged in ferocious battles for control of Kiev, and did not respond to Riazan’s appeal for help. Over the next three years, Batu’s cavalry was able to attack cities singly, without ever facing a combined Rus army, inflicting the carnage we saw above.

|

|

|

In each case, his men looted, destroyed, and killed without mercy. Many towns lost most of their population; able‑ bodied survivors were deported to slavery or to service in Batu’s army.

Eventually Batu withdrew, concluding that direct occupation of such unfamiliar forested territory was beyond him. He set up the capital of his domain (ulus ), usually called by historians the Golden Horde, at Sarai on the lower Volga. From there, he and his successors fashioned a system of dominion over the Rus principalities. They awarded each ruling prince a iarlyk (the right to rule), after a symbolic ceremony of submission. In selecting a successor for each principality, the Golden Horde followed wherever possible the established Kievan principles – but kept the final decision in their own hands. They appointed to each prince a Mongol tribute‑ collector and a viceroy, who carried out a census of the local population – an indication of a highly developed administrative system – to ensure that the people paid tribute to Sarai and contributed recruits to a militia or to a forced labour brigade.

Traditionally, Russians have regarded the Mongol overlordship as an unmitigated disaster. Recent research suggests, however, that, after the initial shock and destruction, it had compensations, even though for several generations it imposed a heavy burden on the Rus population, against which townsfolk periodically rebelled. The Mongols restrained princely feuding. They built and maintained a network of communications, together with postal relay stations, superior to anything that had existed in Kiev. Through it, they plugged Rus into a Central Asian trading network which extended to China, the world’s wealthiest civilization. This trade laid the basis for an economic recovery which gathered pace during the 14th century. The princes who cooperated with the Mongols did especially well: their authority was guaranteed, and they received Mongol support against any rebellion in their territories.

For the Orthodox Church, the Mongol dominion was almost a golden age. The Mongols were on principle tolerant in religious matters, and later themselves became Muslims. They granted the church immunity from tribute and from the obligation to deliver recruits for military and labour service. It was able to accumulate extensive landholdings and vassals. Much of the work of opening up new territories was accomplished by monasteries, which thus became nurseries of both spiritual and economic power. Moreover, with the fragmentation and subjugation of secular authority, the church was the only institution able to speak for Rus as a whole. The Kiev Metropolitan regarded himself as the custodian of its integrity: he took the title Metropolitan of All Rus, and spent much of his time travelling round the various dioceses.

|

|

|

Meanwhile, Novgorod was going its own way. Its far northwestern forest location deterred the Mongols from attacking it. Its prince, Alexander (r. 1236–63), negotiated skilfully with them, and in return for paying an ample tribute received a special charter guaranteeing the city’s right to govern itself. He had good reason to mollify the Mongols, for his western frontier was threatened by the Swedes; he defeated them in 1240 in a battle on the River Neva – hence his nickname Nevskii. In addition, the Teutonic Knights were trying to block Novgorod’s lucrative trading routes in the Baltic. When they advanced towards the city itself in 1242, Alexander overcame them in battle on the frozen Lake Peipus. The scale of the battle may have been exaggerated by later chroniclers, but its significance cannot be. It established the River Narva and Lake Peipus as a permanent boundary between Eastern and Western Christianity.

Alexander’s younger son, Daniil, became ruler of the new principality of Moscow. During the early 14th century, he and his successors succeeded in establishing themselves as the favoured recipients of the iarlyk of Great Prince, even though, as scions of a cadet Riurikovich line, they did not qualify under the Kievan succession rules. Daniil’s son, Ivan I (Ivan Kalita, or ‘moneybags’, r. 1325–41), received the iarlyk in 1328, having seen off a rival from Tver. He practised unswerving loyalty to the Golden Horde, and used his function as their tribute‑ gatherer to enrich his own principality. By subsidizing neighbouring princes, he was able to attract their support and that of their trading towns, and in some cases actually integrate their territories into his own. Gradually, Moscow ceased to observe the Kievan dynastic rules and went over to straightforward patrimonial succession, from father to eldest son. The importance of doing so was underlined when in 1425, on the death of Vasilii I, his brother contested the succession of his son, and plunged Muscovy into a civil war which lasted nearly thirty years. Later princes and their boyars (leading warriors) were determined to prevent any repetition of this disaster.

The recovery of Rus took place not only in the north and east. The south‑ western principalities, notably Galicia and Volynia, allied themselves with Lithuania, which defeated the Golden Horde at the Battle of Blue Waters in 1362, and was able to establish its authority over Kiev and most of the original heartland of Rus. From the late 14th century, Lithuania, for its own protection, sought union with Poland, to form what at the time was the largest kingdom in Europe. The Lithuanian princes accepted the Catholic religion, though many of their people remained Orthodox. In this way, the western and south‑ western principalities of Kievan Rus adopted an elite Latinate Polish culture, which distinguished them from those of the north and east. The language spoken in the west, initially known as Rusin (Ruthenian), evolved into modern Belorussian and Ukrainian. Eventually, their territories became contemporary Belorussia and a large part of Ukraine.

Since the Metropolitanate was the most important ‘all‑ Rus’ institution, its location and powers were vital to the development of Kievan Rus’s successor states. Kiev itself lost its ascendancy because it was especially vulnerable to steppe raids. In 1325, the Metropolitanate relocated to Moscow; Metropolitan Petr, who made the move, was subsequently canonized with the support of Ivan Kalita, and his tomb became a pilgrimage site. This was a crucial moment: from then on, Moscow became the centre of Russian Orthodox Christianity, though at times contested by Kievan Metropolitans with Lithuanian backing.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, monasteries multiplied and acquired extensive new lands in the northern and eastern forests. Their motive was both spiritual and economic. When young monks became discontented with the discipline in their home foundations, they would break away to set up their own skit (hermitage) further into the forest, where to achieve spiritual concentration they could be alone or share divine worship with just a few like‑ minded colleagues. In the course of time, other devotees would join them, build their own huts or shelters close by, and so a whole new monastery would appear. The most skilled and experienced monks became revered elders (startsy ), whose spiritual counsel was sought by believers from all ranks of society. Dostoevsky depicted one as Father Zosima in his Brothers Karamazov.

|

|

|

Such was the biography of St Sergy of Radonezh, who left home with his brother and built a chapel deep in the forest. He acquired a reputation for spiritual insight, and gradually other monks and seekers joined him. Eventually, they set up a full‑ scale monastery, of which they invited him to become the abbot. Reluctantly, and only on the insistence of the local bishop, he agreed. His foundation later became the Lavra of the Holy Trinity and St Sergy, future site of the Moscow Patriarchate and centre of Russian Orthodoxy.

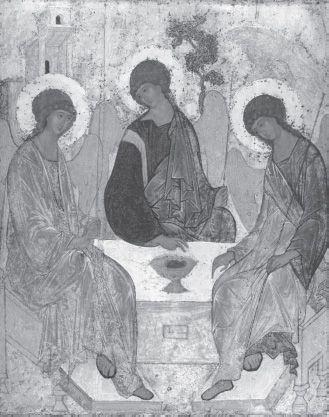

The search for spiritual peace and concentration also inspired icon painters associated with the Moscow princely court and the Trinity Lavra. Feofan the Greek and his pupil, Andrei Rublev, developed Byzantine iconic models, making their figures less monumental, more graceful and expressive in their gestures and appearance. Rublev’s Trinity is perhaps the best known of all Orthodox icons: its light blue colouring, the meek and trusting way the three angelic figures respond to each other, express the spiritual peace and mutual communion (later known as sobornost ) which has remained an ideal for Russian believers.

|

|

|