|

The end of the USSR

|

|

|

|

By the mid‑ 1980s, the Soviet Union faced a serious internal crisis. It was failing to sustain the two major ‘social contracts’ on which its townsfolk depended: cheap food in return for low pay, and give and take between Russians and non‑ Russians.

The man who became CPSU General Secretary in March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev, took over the views of the International Department. He had become convinced that the USSR was not increasing its security by accumulating nuclear and conventional weapons, but on the contrary undermining it by presenting to the outside world an ‘enemy image’, which provoked other powers to rearm against it. His ‘new thinking’ in foreign policy led him into a series of agreements with US President Reagan, in which both sides made deep cuts in their nuclear and conventional arsenals. At the United Nations, he explicitly renounced the ‘primacy of the class struggle’, which had hitherto been at the core of Marxist‑ Leninist doctrine, and called for ‘a world without violence and wars’ and ‘dialogue and cooperation for the sake of development and the preservation of civilisation’.

Internally, he launched a campaign against corruption and criminality in the nomenklatura elite. He encouraged glasnost (openness), so that ordinary citizens could denounce the misdeeds of their superiors. As his campaign advanced, he became convinced that his efforts were being resisted by what he called ‘a managerial stratum, a ministerial and party apparatus which. . . does not want to give up its privileges’. The Chernobyl nuclear explosion of April 1986, whose seriousness officials tried to conceal from him, confirmed his suspicion. Within a few months, he had broadened glasnost into something more like freedom of speech. He also instituted perestroika (political reform), allowing oppositional political movements to disseminate their ideas, and eventually to take part in elections too. Newspapers began openly to criticize government policy. Sakharov was permitted to propagate his ideas freely, but so were nationalists, Russian and non‑ Russian. Solzhenitsyn published his three‑ volume Gulag Archipelago, which gave a fuller account than ever before of the terrible truth about Stalin’s penal empire. A climax was reached in May 1989, when a new Congress of People’s Deputies opened: one after another, speakers denounced the ruling class’s abuses of power. It was televised live, and much of the population took time off work to watch, fascinated and appalled by the spectacle.

It soon became apparent, though, that the Soviet Union could not continue in anything like its present form if there were free speech and pluralist politics. As in the past, the bonds between the ruling class and the mass of people were too brittle to withstand serious strains. Besides, the ‘outer empire’ began to crumble even more quickly under the same pressures, until in 1989 the Berlin Wall fell, and a series of mostly peaceful revolutions brought non‑ Communist parties to power. The Warsaw Pact fell apart.

|

|

|

Inside the USSR, the strain fell first on the economy. Gorbachev launched a reform which legalized private economic enterprises. He intended that they should complement the planned state economy, but in practice they took advantage of shortages to offer higher prices to suppliers and charge customers more. As a result, they sucked goods out of the state economy; ordinary consumers could no longer afford everyday purchases. To make matters worse, the economic reforms also disrupted the informal practices by which people had received goods through their workplaces or personal networks. By 1990, it began to look as if routine food supplies might not reach the major cities.

Relations between the nationalities also suffered. The incongruity of simultaneously fostering and suppressing national consciousness now became obvious. Glasnost and political freedom brought festering enmities to the surface. Popular Fronts formed to express the ethnic grievances of the non‑ Russians. The Baltic republics, whose population had never fully accepted their 1940 incorporation into the USSR, began to demand autonomy, then full secession. Armenians and Azerbaijanis denounced each other, then actually went to war over Nagornyi Karabakh, a territory controlled by Azerbaijan where most of the population was Armenian. Abkhazia demanded secession from Georgia, while Georgia denounced Moscow for encouraging the Abkhazians. In April 1989, the Soviet army had to be called in to deal with massive demonstrations in Tbilisi. It killed at least twenty people, and a public enquiry was launched to investigate its actions.

These ethnic conflicts cast doubt on the viability of the Soviet Union as a federation of ethnically named republics. They also raised the question of the legality of turning the military against unarmed civilians. Commanders became nervous of using force to disperse rioters: they feared they might be held legally responsible for the resulting casualties.

These two developments came together in the Soviet Union’s final crisis, which unexpectedly turned out to be a clash between Russia and the Soviet Union. Russians had long been aware that the non‑ Russian republics were becoming less hospitable homelands for them. In the late 1980s, their gradual exodus turned into a flood. Russians, who had taken it for granted that they were the dominant nationality and had not needed to defend their own identity, started to form their own organizations.

They had a problem, though: it was by no means clear what their national identity consisted of. There was still no coherent narrative of ‘Russia’. Some Russians considered their country essentially an imperial state; others identified with its culture, religion, or ethnic traditions. Some Russian nationalists idolized Stalin as a great leader; others reviled him as the destroyer of the Russian peasantry and the Orthodox Church. Divided by their own heritage, Russian nationalists could not cooperate with one another, until Gorbachev’s reforms threatened the actual break‑ up of the Soviet Union. By then it was too late.

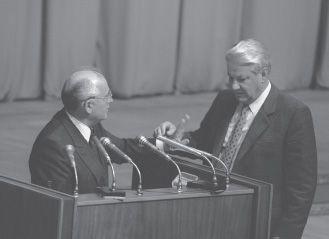

Russia was not only a nation. It was also an institution, albeit a powerless one, within the USSR, the RSFSR. Gorbachev’s reforms gave it real power for the first time, and Russian political movements sprang up, both liberal and nationalist‑ imperialist. At the liberal end, in March 1990 Democratic Russia won many seats in the RSFSR Congress of People’s Deputies, and their spokesman, Boris Yeltsin, gained a perfect platform to denounce the CPSU and demand that Russia be allowed to run its own affairs. In June 1991, he was popularly elected President of the Russian Republic.

|

|

|

The nationalist‑ imperialists also formed their own political parties, which brought together environmental associations, cultural societies, military‑ patriotic organizations, and Russian ‘international fronts’ from the non‑ Russian republics. Their Patriotic Bloc fared poorly in the 1990 elections, but continued to warn of the dangers to which Gorbachev’s peace‑ loving policy had exposed the Soviet Union. The reunification of Germany and its integration into NATO especially infuriated them: everything the Soviet Union had gained by its victory in the Second World War was, they claimed, now lost or jeopardized.

At the highest level of the CPSU, the nationalist‑ imperialists naturally had allies, who were becoming increasingly alarmed at Gorbachev’s policies. When he tried to negotiate a new Union Treaty, which would radically redefine the relationships between the Union and the constituent republics, they decided to strike. On 19 August 1991, they formed an Emergency Committee, put Gorbachev under house arrest, and declared a state of emergency. They brought tanks into central Moscow to take the White House, home of the Russian parliament. They neglected, however, to arrest Yeltsin, who clambered on top of one of their tanks and denounced their coup, declaring it a ‘crime against the legally elected authorities of the Russian Republic’.

|

|

|