|

Chapter 1. Kievan Rus and the Mongols

|

|

|

|

Chapter 1

Kievan Rus and the Mongols

In 1237, Mongol invaders attacked the town of Suzdal.

They plundered the Church of the Holy Virgin and burned down the prince’s court and burned down the Monastery of St Dmitrii, and the others they plundered. The old monks and nuns and priests and the blind, lame, hunchbacked and sick they killed, and the young monks and nuns and priests and priests’ wives and deacons and deacons’ wives, and their daughters and sons – all were led away into captivity.

Such images have haunted the minds of Russians over the centuries. They have been re‑ enacted within living memory in the German invasion of 1941. Whatever else they may have wanted, Russians have always longed for security from terrifying and murderous assaults across the flat open frontiers to east and west. They could not have that security, though, without restraining the feuding of their own internal strongmen. That was the need which motivated the creation of the first Rus state, more than three centuries earlier. The Primary Chronicle, the first East Slav foundation narrative, reported of the 9th‑ century Slav tribes that

there was no law among them, but tribe rose against tribe.

Discord thus ensued, and they began to war against one

another. . . . Accordingly they went overseas to the Varangian Russes.

[And they] said to the people of Rus ‘Our whole land is great and

rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us. ’

Probably this was not a single event but a gradual process by which scattered tribes accepted Varangian, or Viking, rule in the interests of peace, security, and stable commerce. The Vikings established fortified urban settlements on the trading route from Scandinavia to Byzantium along the rivers Volkhov, Dvina, and Dnieper. At the southernmost of these settlements, Kiev, they established a capital city from where their kagan (later Great Prince) could enforce his authority over unruly tribes. It forms the birthplace of two of today’s sovereign states, Russia and Ukraine. Around Kiev they built a semi‑ circle of fortresses to defend it against nomadic raids. They intermingled readily with their subjects and adopted their tongue, so that a common East Slav language and culture emerged, albeit one with a marked social hierarchy: the prince and his druzhina (armed henchmen) formed the elite.

This fixing of authority and culture made life safer and more prosperous: a lively commerce and settled agriculture developed. Kinship faded as the basic principle of social organization, and the names of tribes disappeared from the Chronicles, to be replaced by urban and village communities. The princes awarded their warriors the right of kormlenie, that is to be supported (literally: fed) by local communities in return for guaranteeing protection. This was a variant of the ‘gift economy’; it gave local communities a means to get to know their masters, gauge their reactions, and establish – or sometimes not – some mutual trust and a give‑ and‑ take relationship with them.

|

|

|

To regulate their own affairs, village communities had their own assemblies, for which the term mir, meaning peace or harmony, gradually came into use. The urban assemblies were known as veche: only their support or ‘acclamation’ rendered a prince’s authority fully legitimate. All male citizens were members of the veche, and they had both the right and duty to take up arms in defence of the community.

Establishing a unified kingdom, however, proved more difficult. The various sons of the Kievan Great Prince regularly fought one another for the succession. Efforts to curtail these feuds resembled those of Charlemagne’s successors, who were also trying to suppress lesser princes and unruly tribes. The best way to establish law and order and to generate mutual solidarity was to accept a monotheistic religion. That is what Prince Vladimir (r. 978–1015) did in 988 by accepting the Byzantine form of Christianity. It offered attractive assets to a prince seeking to consolidate his authority: it condemned blood feuds and it justified the princely imposition of law, order, and peace. Two of its first saints, Boris and Gleb, sons of Vladimir, were said to have been murdered by rivals because they declined to participate in dynastic feuds. As it extended its network of parishes, the church also provided the most effective way of disseminating both moral concepts and observance of the law.

A close relationship with Byzantium was especially beneficial to a people who already traded with it. Orthodox Christianity had other advantages: it accepted partnership with secular authority, and its liturgy was conducted in a language akin to the vernacular, so that it was closer to the people than Latin Christianity. On the other hand, after the Byzantine and Roman churches split apart in the 11th century, Orthodoxy lost its ecumenical contact with much of Central and Western Europe.

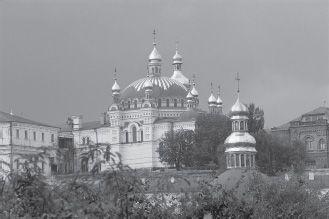

To coordinate the sinews of authority, Vladimir dispersed his sons to various regional bases within his realm. Each had a druzhina, entitled to kormlenie from local communities. Vladimir’s work of consolidation was continued by his son, Iaroslav (r. 1019–54), who rebuilt Kiev as an imposing capital city, with stone fortifications, its own Cathedral of St Sophia, named after Byzantium’s principal church, and a Golden Gate for ceremonial entry. The Kievan Caves Monastery became a centre of Christian learning and culture, and over several decades in the 11th and early 12th centuries, it produced the Primary Chronicle, which identified the Kievan realm as the joint enterprise of Vladimir’s Riurikovich dynasty (called after the first Varangian prince, Riurik). Iaroslav promulgated the first Rus‑ ian law code, the Russkaia Pravda. Pravda is a key word for understanding Russian culture: it means not only truth, but also justice and what is right according to God’s law. The code’s main contribution was to severely restrict blood feud and supplant it with a closely calibrated scheme of fines for murder, injury, insult, or violation of property. The capacity to impose such fines presupposed both strong central authority and a stable monetary system.

|

|

|

At the northern end of the trading route from Scandinavia to Byzantium, the city of Novgorod developed as a major economic centre. It gained control over the immense territories of the far north and east, and it enforced tribute on the local Baltic and Finno‑ Ugrian peoples. From the huge forests, the Novgorodians could sell timber, furs, wax, and honey both southwards to Kiev and Byzantium, and westwards to the Baltic and Germany through the Hanseatic League. It had its own Cathedral of St Sophia and its own archbishop, who was second only to the Kiev Metropolitan. Its veche was especially influential and frequently reasserted its right to elect its own prince, whatever the dynastic arrangements laid down from Kiev.

|

|

|