|

1 – power. 2 – passage. 3 – passenger. “Power” refers to the forces that move fetus through the birth canal. This is mostly accomplished by the regular rhythmic uterus contractions and known as labor pains.

|

|

|

|

1 – power

2 – passage

3 – passenger.

“Power” refers to the forces that move fetus through the birth canal. This is mostly accomplished by the regular rhythmic uterus contractions and known as labor pains.

The “Passage” is the space that is available for the fetus to pass through. This passage is formed by maternal pelvic bones – her physical anatomy. The overall shape and architecture of maternal pelvis is determined by her body type and is constant throughout her life, including labor and delivery. Some hormones released during pregnancy (such as relaxin) allow for increased mobility of certain joints of the pelvis during pregnancy and childbirth and it is physiological changes, specific for gestation and reproductive process. If the joints in the pelvis are unable to move properly to create space or maternal pelvis is smaller then normal one (contracted pelvis), the birth is more likely to be difficult for both mother and baby.

The “Passenger” is the fetus. The process of fetus moving through the passage is dependent on fetus size and position in relation to the mother. The ideal position for the baby is head down, chin tucked, with their body/back aligned on the left side of the mother. The position known as left occiput anterioir presentation (LOAP). This position typically allows for the best set-up for an easier labour and delivery. In case of disparity in the relation between passenger and passage sizes during the process of labor the descent of the fetus head through maternal pelvis may be slow or impossible. Abnormal labor (CPD, dystocia of labor) develops. Labor forces are also important for the process of fetal descent through the birth canal and delivery of a healthy child.

Cephalo-pelvic disproportion (CPD) is a dynamic situation which develops only during labor due to:

· anatomically contracted pelvis

· big fetus

· malpresentations (brow, vertex presentation)

· postmaturity, in which there is no possibility of molding the head.

Diagnosis of CPD

The diagnosis of CPD may be made during labor, more over after the opening of the cervical canal by 5-6 cm, rupture of amniotic membrane and head pressed to the pelvic inlet plane. But suspicion may arise earlier.

The main symptoms of CPD are:

· the character of head engagement (corresponding to the pelvic architecture);

· Vasten’s symptom is brim-full or positive;

· Zangemeister’s diameter is the same as external conjugate, or bigger;

· symptom of bladder pressing against the symphysis pubis;

· threatened rupture of the uterus.

The Vasten’s sign can be used to determine the CPD after engagement of the head. The palm of an examining hand is placed on the surface of the symphysis and then moved upwards onto the region of the presenting part. If the anterior surface of the head is above the symphysis plane, it indicates the marked disparity in the relation between the fetal skull and maternal pelvis dimensions (a positive Vasten’s sign). Labor cannot end spontaneously. If the disproportion is not pronounced, the anterior surface of the head levels with the symphysis (Vasten’s sign is brim-full). If the labor pains are effective and the head molding is adequate, labor can end spontaneously, but the risk of complications is high. If uterine inertia develops, spontaneous delivery becomes impossible, especially if the fetal head is large. In complete absence of any CPD, the anterior surface of the head is below the symphysis plane (Vasten’s sign is negative) and labor can usually end spontaneously (Fig. 207).

|

|

|

a. b. c.

Fig. 207. The Vasten’s sign: a – positive; b - Vasten’s sign is brim-full; c - Vasten’s sign is negative

Zangemeister suggested that the presence and degree of elevation of the anterior surface of the head over the sacrum might be measured by a pelvimeter with the parturient lying on her side. The external conjugate is first measured, and the pelvimeter bulb is often moved from the symphysis onto the most prominent point of an anterior surface of the fetal head (the posterior bulb of pelvimeter remains at the forming point). Normally the external conjugate exceeds the distance from the head to the suprasacral dimple by 3-4 cm. If there is a CPD, the latter distance is greater than the external conjugate. If both distances are identical, the CPD is not manifested and prognosis is indistinct. Labor can end spontaneously if the labor pains are intensive and the head molding is adequate.

Three degrees of CPD are distinguished.

The 1st degree, named “relative disproportion” is: Vasten’s sign is negative and Zangemeister’s distance is less than external conjugate while the pelvis is anatomically contracted, or head is large. The head molding is good, labor pains are effective, and the patient is not tired, fetal condition is not altered. Spontaneous delivery is possible.

The 2nd degree, named “moderate disproportion” is: Vasten’s sign is brim-full, Zangemeister’s distance is “equal” (identical), the molding of the head is strong, and there is the remaining of the head on one of the planes of the pelvis for a long time (> 1hour). Any abnormalities of labor pains may occur, the bladder is “pressed”, the patient is tired, and the fetus may have distress. Urgent cesarean section is indicated.

The 3rd degree (pronounced CPD) – Vasten’s sign is positive; Zangemeister’s distance is bigger than external conjugate. There is no molding of the head, no descending of the head. The maternal and fetal general condition may worsen; clinical features of threatened rupture of the uterus appear. Emergent cesarean section is indicated.

Self Test

1. The degree of narrowing in transverse contracted pelvis is distinguished depending on:

A. size of transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet

B. size of anteroposterior diameter of pelvic inlet

2. The degree of narrowing in flat pelvis is distinguished depending on:

|

|

|

A. size of anteroposterior diameter of pelvic inlet

B. size of transverse diameter of pelvic inlet

3. Which of the following is the 2nd degree of narrowing?

A. true conjugate is 11cm

B. true conjugate is 9 cm

C. true conjugate is 8 cm

D. true conjugate is 5 cm

4. An anatomically contracted pelvis may be diagnosed

A. during labor

B. at any time

5. Anteroposterior diameter of pelvic inlet is reduced in:

A. simple flat pelvis

B. rachitic flat pelvis

C. generally contracted flat pelvis

D. flat pelvis with reduced anteroposterior diameter of the 2nd plane

6. All anteroposterior diameters of pelvis are reduced in:

A. simple flat pelvis

B. rachitic flat pelvis

C. generally contracted flat pelvis

D. flat pevis with reduced anteroposterior diameter of the 2nd plane

7. CPD pelvis may be diagnosed:

A. before pregnancy

B. in early terms of gestation

C. in late terms of gestation

D. during labor

E. after labor

8. CPD may be complicated by:

A. premature delivery

B. small-for-date fetus

C. threatened rupture of the uterus

D. Preeclampsia and eclampsia syndrome

9. Spontaneous delivery is possible in case of:

A. a relative CPD

B. a moderate CPD

C. a CPD

10. CPD may be diagnosed:

A. at any time

B. in early terms of pregnancy

C. in late terms of pregnancy

D. during the labor

12. The sign of CPD may be evaluated after:

A. the beginning of the first stage of labor

B. the opening of cervical canal by 2-3 cm

C. the opening of cervical canal by 5-6 cm

D. the fetal head has passed into the pelvic cavity

CHAPTER 32. MATERNAL INJURIES IN LABOR AND DELIVERY

Maternal traumata in labor may be classified depending on tissue (mucous tunic, muscles, bones), localization (uterus, cervix, vagina, vulva, perineum), degree (the 1st, 2nd, 3rd), damage (hematoma, fissure, laceration, rupture, inversion, fistulae, separation of joint).

Lacerations of the perineum, vulva, vagina and the cervix often occur during labor and delivery. Hematomas of the skin, mucous membrane, separation of the pelvic bones, urogenital and rectovaginal fistulae appear rarely in pathological labor.

Lacerations of the Perineum, Vulva, and Vagina

The expulsion stage of labor is accompanied by a marked distension of the vagina, vulva, and perineum. These parts of the birth canal are therefore often injured during labor and delivery (Fig. 208).

Fig. 208. A – overdistension of the perineum with the nascent head

Fig. 208. A – overdistension of the perineum with the nascent head

B – rupture of the perineum with the nascent head

Lacerations of the Perineum

The factors predisposing to lacerations of the perineum are as follows:

1. lack of tissue elasticity in ‘elderly’ primipara, scars remaining after previous delivery, and high perineum;

2. the fetal head passes through the vulvar ring by one of its diameters other than the smallest one; this occurs with premature extension of the vertex and with excessively large fetal head;

3. operative delivery (forceps delivery, etc. );

4. contracted pelvis, especially flat rachitic pelvis (rapid delivery) and infantile pelvis (narrow pubic angle);

5. premature extension of the vertex and rapid delivery of the head.

The injury never occurs without warning and is usually preceded by changes that indicate the approaching laceration. As the thrust on the perineum increases with the progress of the fetal head, it becomes protruded like a dome, cyanotic and edematous. The skin then turns pale, lustrous, and minor fissures develop on the perineum. These changes (protrusion of the perineum, cyanosis, edema, pallidness) are signs of threatened laceration of the perineum.

A perineotomy should then be performed, since the smooth edges of the cut wound will heal sooner than the lacerated tissues.

The following classification of perineal lacerations is offered:

First degree. The posterior fourchette is lacerated (the small area of the perineal skin and the vaginal wall are involved); the perineal muscles remain intact.

|

|

|

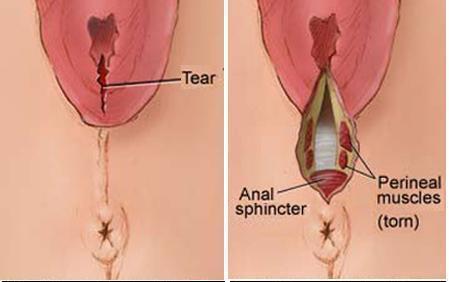

Second degree. The perineal skin, the vaginal walls and the perineal muscles (except the external rectal sphincter) are lacerated (Fig. 209).

- 2.

Fig. 209. 1. The first degree of perineal laceration: the small area of the perineal skin and the vaginal wall are involved, the perineal muscles remain intact; 2. The second degree of perineal laceration: the perineal skin, the vaginal walls and the perineal muscles (except the external rectal sphincter) are lacerated.

Third degree. In addition to the above described lacerations, the external sphincter ani (incomplete of third-degree tear), and sometimes the rectum wall are also involved (complete of third-degree tear) (Fig. 210).

A rare complication of labor is the central rupture of the perineum, while the posterior fourchette remains intact. The fetus is then delivered not through the pudendal cleft but through the opening formed by the ruptured central perineum (Fig 211).

Injury of the soft reproductive tract, the perineum included, is fraught with danger of infection. Furthermore, even insignificant lacerations of the perineum predispose to lowering and prolapse of the reproductive organs.

Faecal and gas incontinence develops in lacerations of the third degree.

All perineal lacerations should be repaired.

Fig. 210. The Third degree of perineal lacertion: the external sphincter ani and the rectum wall are also involved

Fig 211. The central rupture of the perineum

Repair of Perineal Lacerations

Perineal lacerations should be sutured immediately after the delivery of the placenta. The sooner the lacerations are repaired, the smaller the danger of infection. Suturing is not recommended until the placenta has been delivered because manual invasion of the uterus may become necessary if complications develop in the placental stage of labor.

All rules of asepsis should be observed in the repair of perineal lacerations. The operative field and surgeon’s arms should be cleansed and scrubbed as for obstetrical operation.

A catgut suture should be placed on the upper angle of the wound in the vaginal wall; the ends of the thread should be pulled upwards by forceps. Two forceps are used to clamp the wound edges in the region where the vaginal mucosa converts into the perineal skin. Using the ligature and two clamps, the wound is opened, dried up, and the character of laceration studied. The torn off wound edges should be removed.

The first degree of perineum lacerations are repaired by placing catgut sutures on the vaginal mucosa, and then silk sutures on the perineal skin. Sutures should be spaced at 1 cm intervals. The needle should pass under the entire wound surface; otherwise slits will remain where blood will accumulate to interfere with healing. The wound should be ligated so that its edges tightly contact each other. In such case the wound would be healing.

The order of repairing the second degree perineal lacerations is as follows: the upper angle of the wound is first sutured, and then the lacerated perineal muscles are repaired by several buried catgut sutures (the sutures should not involve the skin or mucosa). The vaginal mucosa should then be sutured up to the posterior fourchette. The ligature ends (except at the posterior fourchette suture) should be cut off. The latter suture is pulled upward to facilitate suturing of the perineal skin. The perineal skin should be sutured with a silk thread and its ends cut off. (Metal staples can also be used. ) The sutured wound should be treated with an iodine tincture (Fig. 212, 213, 214, 215).

|

|

|

Fig. 212. Closing the vaginal sulci

Fig. 213. Repairing of the perineal muscles

Fig. 214. Closing the wound

Fig. 215. Completion of the operation.

In repairing the third degree perineal lacerations, the injured wall of the rectum should first be sutured (Fig. 216). The separated ends of the lacerated rectal sphincter should then be identified and sutured (Fig. 217). Next the order is the same as in repairing the second degree perineal lacerations.

Fig. 216. Repairing of the 3rd degree of perineal laceration: Suturing of the rectal mucosa

Fig. 217. Reaching down into the bottom of the sphincter ani.

The postoperative care in perineal lacerations consists in keeping the sutures clean. Sterile gauze should be used to cover the wound (renewed at 3-4 hour intervals). The wound may, however, be kept without gauze covers. The suture should be washed off 3–4 times a day, after which it should be dried up by sterile pad and treated with antiseptic drugs. The suture should also be dried up after washing the external genitalia after defecation or urination. Usual regimen should be recommended for puerpera, they are only forbidden to sit.

The patient should be recommended a light diet: sweet tea, broth, and other digestible food.

In cases with the third degree perineal lacerations 2-3 capsules of loperamid should be given to the puerpera every day during six days in order to keep away stools. Approximately on the sixth day of postpartum period castor oil may be given or an oil enema may be administered.

Silk thread should be removed in 5 or 6 days. The patient is allowed to rise on the following day after removal of the sutures.

Lacerations in the region of the clitoris and lips are often accompanied by marked bleeding. The laceration of the cavernous body may cause a considerable loss of blood. All lacerations should be repaired. When the clitoral area is repaired, a metal catheter should be inserted into the urethra to preclude its involvement in the suture.

Lacerations of the Vagina

Insufficient distensibility of the vaginal walls, infantilism, operative parturition, delivery by extended vertex, large fetal head, etc. are among the causes of vaginal lacerations. The lower third of the vagina is commonly lacerated (along with laceration of the perineum).

Lacerations of the vagina are usually revealed by specular inspection and sutured by catgut. Lacerations of the lower third of the vagina may be repaired with separation of its walls by the fingers of the left hand.

Lacerations of the Vagina

Insufficient distensibility of the vaginal walls, infantilism, operative parturition, delivery by extended vertex, large fetal head, etc. are among the causes of vaginal lacerations. The lower third of the vagina is commonly lacerated (along with laceration of the perineum).

Lacerations of the vagina are usually revealed by specular inspection and sutured by catgut. Lacerations of the lower third of the vagina may be repaired with separation of its walls by the fingers of the left hand.

Hematoma of the vulva and vaginal walls

Blood vessels may rupture during delivery and the subcutaneous connective tissue of the external genitalia or the vaginal submucosa will be effused with the blood, while the overlying coat remains intact. The skin and the mucosa overlying thus formed hematoma become red-blue and if much blood accumulates in the tumor, the tissues become strained and painful.

Treatment of small hematomas is expectant. An ice bag is first placed on the affected area but later a careful treatment with physiotherapeutic warmth should be given. If hematoma swells rapidly, the skin should be incised, the hematoma emptied, and the broken vessel tied up. The incised site should then be repaired.

Rupture of the Cervix

Because of effacement and taking up the cervix, which occur in the first stage of labor, the margins of cervical os are strongly thinned. Superficial lacerations of the cervical os do not frequently cause marked bleeding and usually remain unidentified. But the uterine cervix may also rupture which occurs especially often in pathological labor. The rupture is accompanied by considerable bleeding and other unfavourable consequences. The cervix ruptures on its lateral sides, especially on the left one. The rupture may extend to the vaginal fornix, pass into it, and reach the parametrial tissues. Three degrees of the cervical rupture are distinguished: in the first degree the cervix ruptures to a length not more than 2 cm; in the second degree this exceeds 2 cm but does not reach the fornix by 1 cm; in the third degree the ruptured area reaches the fornix and passes onto it (onto the upper part of the vagina).

|

|

|

Blood vessels are injured in the deep rupture of the cervix to cause bleeding which is often profuse and endangers the mother’s life. The bleeding is normally external; if the rupture is deep, part of this blood accumulates in the parametrial tissues to form a hematoma.

Bleeding usually develops after delivery of the fetus, but it is difficult to locate the source of bleeding until the placenta is delivered. As soon as the placenta has been expelled, it is easy to differentiate between bleeding from the lacerated cervix and the placental site. The rupture of the cervix is characterized by persistent bleeding from a contracted firm uterus. In order to establish a definite diagnosis, the cervix should be inspected by specula. The margins of the cervical os are held by the forceps and inspected step by step.

Spontaneous and traumatic (surgical) ruptures are differentiated. A spontaneous rupture is favoured by rigidity of the cervix, in “elderly” primipara in particular, excessive distension of the cervical os margins (large fetus, extended vertex), precipitate labor, prolonged compression of the cervix in contracted pelvis with disturbance of normal transport of nutrients to tissues.

A traumatic rupture of the cervix develops in operative parturition (forceps delivery, podalic version, extraction of the fetus, destructive operations on the fetus, etc. ). The rupture of the cervix is dangerous not only because of bleeding. Unrepaired lacerations or ruptures get infected and a puerperal ulcer is formed in an open cleft, which is the source of further spread of puerperal infection. As the unrepaired lacerations heal, scar tissue is formed which may become the cause of cervical eversion (ectropion). The eversion later causes chronic inflammation of mucosa in the endocervical canal and erosion of the uterine cervix. Unrepaired lacerations may result in isthmico-cervical incompetence leading to habitual abortions.

Treatment

The lacerated or ruptured cervix should be repaired by suturing. The sutures should be placed immediately after inspection of the cervix and discovery of lesions. The cervix should be pulled by the forceps toward the introitus and moved aside (in the direction opposite to the affected side). Suturing should begin from the upper angle of the rupture (the first suture should be placed slightly above the rupture) to the margins of the cervical os; the mucosa of the cervix should not be involved in the suture (Fig. 218).

If the upper edge of laceration is difficult to identify, the first suture should be applied slightly below, and the ends of the ligature should be pulled down; the upper angle of the wound will thus be revealed and become accessible for suturing. Catgut should be used to correct cervical lacerations and ruptures. The ends of ligatures should be cut off.

Fig. 218. Suturing of the cervix.

Rupture of the Uterus

The disruption of integrity of the uterine walls is known as rupture of the uterus. If all layers of the uterus, i. e. endometrium, myometrium, and peritoneum break, the rupture is complete. The cavity of a completely ruptured uterus opens into the abdominal cavity. If only endometrium and myometrium are involved, the rupture is incomplete. A complete (penetrating) rupture of the uterus occurs more frequently than an incomplete one.

A comparatively thin lower uterine segment usually ruptures, but the upper segment and even the fundus can rupture as well. The rupture may occur along the line of the cervix attachment to the vaginal fornices; this is actually the separation of the uterus from the vaginal fornices.

Spontaneous and traumatic ruptures of the uterus are distinguished. A spontaneous rupture occurs without any extraneous cause, while a traumatic rupture is mainly due to improper operative intervention.

The rupture of the uterus is one of the most dangerous complications of labor. Even with modern obstetrical knowledge the rupture of the uterus not infrequently results in death of the mother and intrauterine fetus. The danger depends on acute loss of blood and shock. Blood is lost from the vessels which break together with the uterine wall. The larger the disrupted vessels, the stronger the hemorrhage. Another source of bleeding is the vessels of the placental attachment site. The placenta usually separates at rupture of the uterus and the vessels of the uterine wall at the site of placental separation start bleeding. The hemorrhage accompanying the rupture of the uterus may be very profuse. The picture of acute anemia is aggravated by traumatic shock which usually occurs at rupture of the uterus, a complete rupture in particular. The shock develops on a background of strong irritation of the nerve endings of the ruptured uterus (especially of its peritoneal coat). The fetus is often extruded from the ruptured uterus into the abdominal cavity where it affects other abdominal organs increasing the danger of developing shock. The fetus would usually die very rapidly because of the placental separation.

The uterus may rupture due to a variety of causes. In the past century (1875) Bandl created a mechanical theory of uterine rupture. In his opinion, which was supported by many other obstetricians, the rupture occurs due to disproportion between the presenting part and the maternal pelvis. This would be usually explained by contracted pelvis, malpresentation (brow, posterior face presentation), a pathological asynclitism, large (gigantic) fetus, hydrocephaly, or transverse and oblique presentations of the fetus.

Violent uterine contractions develop in obstructed labor; the upper uterine segment contracts even more intensely, and the fetus is propelled gradually toward the lower uterine segment where the walls are thinned by distension. The contraction ring (at the junction of the lower and upper uterine segments) rises to higher levels to reach the navel (the ring may also be oblique). As the contractions persist, the lower uterine segment becomes overdistended and ruptures (Fig. 219)

Fig. 219. Excessive thinning of lower uterine segment.

Verbov suggested another theory, according to which an intact uterus never ruptures and the rupture may only develop in the presence of pathological changes in the uterine wall which are responsible for inadequacy of the myometrium. The changes that predispose to the rupture of the uterus are scars resulting from previous cesarean section or other operations on the uterus (enucleation of a myomatous node), injuries associated with previous abortions, degenerative and inflammatory processes in the past history, infantilism, and other abnormalities.

According to modern views, the rupture of the uterus may result from both pathological changes in the uterine wall and mechanical factors. The uterus is more likely to rupture in cases with combination of these defects, i. e. in simultaneous action of several pathological factors (pathologies in the uterus concurrent with obstructed labor).

The uterus usually ruptures in multiparae and very seldom in young primiparae.

The rupture usually occurs during the expulsive stage of labor when obstacles to the progress of the fetus through the birth canal are encountered. In the presence of pathological changes in the uterine wall (scar tissue, inflammatory and degenerative processes), the uterus may rupture during the 1st stage or even at the very beginning of labor. Cases of uterine rupture during pregnancy are also known (due to pathological changes in the uterine wall).

Classification of uterine ruptures

· Depending on time of occurrence:

· Rupture of the uterus during pregnancy

· Rupture of the uterus during labor

· Depending on pathogenesis:

· Spontaneous rupture: a) mechanical (due to disproportion between the presenting part and the maternal pelvis); b) histopathologic (due to pathological changes in the uterine wall); c) combined (due to both pathological changes in the uterine wall and mechanical factors).

· Violent (forcible) rupture of the uterus: a) traumatic (due to external effect during labor); b) combined (due to overdistended uterus and external effect).

· Depending on clinical picture:

· Threatened uterine rupture

· Complete uterine rupture

· Depending on damage:

· Fissure

· Incomplete

· Complete

· Depending on localization:

· Rupture of the fundus

· Rupture of the corpus

· Rupure of the lower segment

· Separation of the uterus from the vaginal fornices

Threatened Rupture of the Uterus

The clinical picture of threatened rupture is very specific in obstructed labor (contracted pelvis, malpresentation of the fetus, large fetus, etc. ) The clinical picture of threatened rupture associated with the presence of mechanical obstacles to the expulsion of the fetus is as follows:

· Labor is violent; the contractions become convulsive in character.

· The lower uterine segment is overdistended, thinned, and painful on palpation.

· The contraction ring stands high (to reach the navel). Its position is oblique.

· The round ligaments of the uterus are very strained and painful.

· The margins of the cervical os become edematous (due to compression). The edema extends to the vagina and perineum.

· Urination becomes difficult due to compression of the bladder and the urethra between the bony pelvis and the fetal head.

· Traces of blood appear in the vaginal discharge to indicate the beginning of tissue injury.

· The parturient is excited, restless (she cries, tosses in bed, grasps the abdomen) and complains of sharp pain.

The clinical picture of threatened rupture due to a scarred uterus (scar on the uterine wall after previous operations) is less distinct, and differs in absence of precipitate labor: the contractions are frequent and painful but not very forceful. Other symptoms, such as overdistension, tenderness of the lower uterine segment, edematous cervix, vagina and external genitalia, disordered urination, etc., are also present but are less distinct than in a threatened rupture due to mechanical cause. In the presence of scars resulting from previous cesarean section the clinical symptoms of threatened rupture are the following: tenderness of the scar during contractions and on palpation, thinning of the scar (niche symptom). Threatened rupture of scarred uterus may be predicted with US of the uterus by evaluation of irregularity of uterine wall, niche appearance on the scar area.

If appropriate medical aid is not rendered, the uterus will inevitably rupture.

Threatened Uterus Rupture Management

When signs of threatened rupture develop the uterine contractions should be discontinued or lessened, and abdominal cesarean section should be performed on the patient.

Ether (or other type of inhalation narcosis) should be given in order to stop or lesson uterine contractions.

The woman should be delivered very carefully with deep anesthesia. If the fetus is alive and there are no signs of infection, a cesarean section should be made. A dead fetus should be dissected and removed by parts. Version of the fetus or application of obstetrician forceps is contraindicated; these operations, or even an attempt to perform them, will inevitably result in the rupture of the uterus.

A Complete Uterine Rupture

A complete rupture is characterized by the following symptoms:

· An extremely severe and acute pain (knife-like pain) in the abdomen is felt by the woman at the moment of rupture.

· Uterine contractions discontinue immediately following the rupture.

· The condition of the patient is sharply aggravated due to increasing anemia and shock. The skin and the visible mucosa become pallid, the face becomes pointed, the pulse is accelerated and weak, the arterial pressure drops. Nausea and vomiting often occur.

· When the uterus disrupts, part or the whole fetus is extruded into the abdominal cavity. Separate parts of the fetus become now directly palpable through the abdominal wall; the presenting part, which was previously engaged, moves upwards and becomes movable. The fetal heart tones are not heard. The contracted uterine body can be palpated by side of the fetus.

· External bleeding is usually not pronounced and sometimes even insignificant. The blood fills the abdominal cavity (a hematoma of the pelvic connective tissue develops in incomplete rupture of the uterus).

In the presence of pathological changes in the uterine wall (for example, in case of scar after previous operation), the rupture may occur because of gradual separation of the tissue. Acute and sudden pain may therefore be absent and contractions do not stop abruptly but lessen gradually. All other signs of the uterus rupture are obvious.

Management of Complete Uterine Rupture

If the uterus has already ruptured, a laparotomy should be performed immediately. The fetus, the placenta and the blood should be removed from the abdominal cavity. The uterus should then be extirpated. In some cases the uterus is repaired by suturing (in young women, if only little time has passed since the uterus was ruptured, and in the absence of infection). Measures to prevent blood loss and shock should be taken during the operation and immediately after it. Blood transfusion, intravenous infusions of physiological saline solution, plasma and albuminous solutions, cardiac preparations should be used.

Prophylaxis of the Uterine Rupture

It consists in adequate organization of obstetrical aid. Thorough observation of all pregnant women is very important in this respect. All women in whom the rupture of the uterus is likely to occur should be given special care. The factors predisposing to the uterine rupture are contracted pelvis, malpresentation of the fetus, post-term pregnancy, large fetus, flaccid abdominal wall and uterus in multiparae, unfavourable obstetrical anamnesis (pathological previous labor, complicated abortions, puerperal and postabortal inflammatory diseases), previous cesarean section and other operations on the uterus.

All women in whom the predisposing factors have been revealed should be hospitalized two or three weeks prior to anticipated labor. Labor should be conducted in the presence of a physician. The parturient should be observed thoroughly during labor so that the signs of threatened rupture are not overlooked.

Inversion of the Uterus

The inversion of the uterus is its turning inside out; the mucosa then becomes the outer layer, while the serous coat becomes the internal layer (the uterus is turned inside out like a finger of a glove). It occurs as follows: the uterine fundus is first impressed into the uterine cavity, then it reaches the cervical os, and finally turns inside out to assume a new position in the vagina (or even outside the pudendal cleft).

The uterus inverts under the following conditions: a) the cervical os is open; b) the uterine walls are relaxed (e. g., in hypotony or atony); c) downward thrust on the uterus (e. g., during extrusion of the placenta) or traction, for example, by the cord. The inversion of the uterus is favoured by: 1) a combination of relaxation of the uterine wall and extrusion of the placenta by the Crede-Lazarevich manoeuvre without preliminary massage of the uterine bottom; (2) traction by the umbilical cord with insufficient contraction of the uterus and a wide open cervix.

Inversion of the uterus after delivery is usually accompanied by grave symptoms, such as acute pain in the abdomen and shock. The skin and the mucosa become pallid, the pulse accelerates, the arterial pressure drops; nausea, vomiting and syncope develop. A bright red inverted uterus appears from the pudendal cleft. Sometimes the uterus is inverted together with the non-separated placenta. A funnel-shaped depression is formed in the lower abdomen. The inversion of the uterus may become the cause of woman’s death.

Treatment. The uterus should be carefully corrected in a heavily anaesthetized patient. The placenta, if any, should be separated from the uterus before restoring its position. The vagina should then be packed with a strip of sterile gauze. Measures to prevent shock and infection should be taken. In case of non-effective restoring the uterus should be extirpated.

Separation of the Symphysis Pubis

During pregnancy the pelvic junctions and ligaments become hydrous due to saturation with serous fluid. This especially holds true for the symphysis pubis. Pelvic junctions may soften considerably in some pregnant. A heavy thrust of the fetal head on the bony ring of the pelvis during labor may cause separation of the symphysis pubis. This is more likely to occur in women with contracted pelvis, giant fetus, and inoperative parturition. Sometimes separation of the symphysis pubis is accompanied by bleeding and injury of the urethra, bladder or clitoris.

The sacroiliac joint may also be affected in complicated (especially operative) labor and delivery.

If the symphysis pubis separates, the woman complains of pain in the region of the symphysis; pain becomes especially annoying on locomotion. The pain intensifies when the legs flexed on the abdomen are abducted. A depression can be palpated between the separated ends of the pubic bones. If necessary, the diagnosis may be confirmed by ultrasound or x-ray examination.

Treatment. Bed rest and tight bandaging of the pelvis are recommended. Bed rest is administered for three or five weeks (sometimes for longer time). The walk in some women is disordered (waddling gait), but this defect is usually corrected in a lapse of time.

Fistulae

Urogenital and rectovaginal fistulae may be formed in pathological labor. Urogenital fistulae are abnormal communications between the bladder and the vagina (vesicovaginal fistulae) or between the urethra and the vagina. An abnormal communication between the bladder and the endocervical canal may be formed in rare cases. In these pathological conditions the urine (or only part of it) is emptied into the vagina and is discharged through the pudendal cleft. Faeces enter the vagina in rectovaginal fistulae. The fistulae are grave complications of labor and cause severe distress in women.

Fistulae are formed due to prolonged compression of the soft tissues of the birth canal and the adjacent organs between the pelvic walls and the presenting part (in contracted pelvis, malpresentations, pathological asynclitism, giant fetus, etc. ). The compression upsets a normal circulation of blood in tissues with their subsequent necrosis and rejection. When the necrotized tissues are rejected a communication between the vagina and the rectum or bladder (urethra) is formed and faeces or urine enter the vagina. This usually occurs on the 5th or 7th day after delivery.

Fistulae may be formed due to injuries of the soft tissues of reproductive tract and adjacent organs (bladder or rectum) inflicted on the women by the surgical tools used in obstetric operations (destructive operations on the fetus, forceps delivery, etc. ). In these cases fistulae are formed immediately after parturition.

The formation of fistulae may be prevented by appropriate conduct of labor. After the loss of amniotic fluid the delay of fetal head moving in one of the pelvic planes for a long time should be excluded. If the head is retained in the inlet, cavity or outlet planes for over two hours, a vaginal examination should be made to establish the diagnosis and to decide which way of parturition is more favourable in a given case. The condition of the bladder should be constantly observed. If urine is retained, the bladder should be catheterized carefully. Even insignificant traces of blood in the urine indicate a threatened fistula and the labor should then be ended operatively.

Fistulae should be treated operatively. Only small fistulae may close spontaneously provided they are managed properly. The treatment then consists in keeping the external genitalia clean, and applying vaseline or other oil, antibiotic emulsion to the external genitalia and to vaginal mucosa (to preclude irritation).

When a urogenital fistula is diagnosed, a permanent catheter for 6-7 days should be inserted into the urethra (the catheter should systematically be removed and sterilized by boiling). Hexamethylenetetramine, antibiotics should be given per os for prophylactic purposes. If the fistula does not close spontaneously, an operation should be made in 4 or 6 months post partum.

Self Test

1. At 1st degreee of perineal laceration

A. the perineal muscles remain intact.

B. the perineal muscles are lacerated.

C. the perineal muscles and external sphincter ani are lacerated.

2. The uterus usually ruptures in

A. multiparae.

B. young primiparae.

3. Rupture is characterized by all the following symptoms, except for:

A. an extremely severe and acute pain in the abdomen felt by the woman at the moment of rupture

B. discontinuation of uterine contractions immediately after the rupture

C. sharp aggravation of the patient’s condition due to increasing anemia and shock

D. disturbances of placental separation in the third stage of labor

4. If the uterus has already ruptured,

A. a laparotomy, removing of the fetus and extirpation of the uterus should be performed immediately.

B. forceps should be applied immediately.

C. vacuum extraction of the fetus should be recommended.

5. The uterus inverts under the following conditions except for:

A. the cervical os is open

B. the uterine walls are relaxed (e. g., in hypotony or atony)

C. downward thrust on the uterus (e. g., during extrusion of the placenta)

D. weakness of labor pains

6. Separation of the symphysis pubis may happen due to:

A. contracted pelvis

B. small fetus

C. weak labor pains

7. The fistulae are formed due to the following reasons except for:

A. anatomically contracted pelvis

B. malpresentations

C. pathological asynclitism

D. giant fetus

E. myoma of the uterine corpus

8. At what degree the ruptured area reaches the fornix and passes onto it?

A. 1st degree

B. 2nd degree

C. 3rd degree

CHAPTER 33. THE MAIN TYPES OF OBSTETRIC OPERATIONS

CESAREAN SECTION

It is an operation whereby the fetus is delivered through the incision in the abdominal and uterine wall. There are a lot of types of cesarean section. It may be large and minor, according to term of pregnancy. Minor cesarean section means the operation in term of 16-22 weeks of pregnancy. Thus, it is done by methods of urgent termination of pregnancy due to a severe complication, when there is no possibility to do therapeutic abortion or there is no time to induce the uterine contractions. Minor cesarean section may be performed by two methods: by dissecting the abdominal wall and by dissecting the vagina in the area of fornix. Most operations are performed by the abdominal access.

The operation which is performed in term of over 22 weeks of pregnancy is named a large cesarean section. Most operations of cesarean section are a large cesarean section.

The types of cesarean section may be subdivided into the following groups:

· intraperitoneal

· extraperitoneal

The first group of operations means those performed through the incision of the peritoneum.

There are some types of such operations:

· Classical method or upper segment operation: the uterus is dissected in the area of corpus (corporal cesarean section).

· Lower segment operation: the uterus is dissected in the retrovesical area, behind the bladder.

· Operations with the temporary or constant protection of the abdominal cavity.

Extraperitoneal cesarean section is the type of operation which is performed in the lower segment without incision of the peritoneum, in the area of vesicouterine pouch.

The operations with protection of the abdominal cavity and extraperitoneal operation are called protective types of cesarean section.

Cesarean section may be performed according to plan, or it may be urgent.

Indications for cesarean section.

Nowadays these are divided into maternal and fetal.

· Fetal indications include:

· Conjoined twins

· Giant fetus

· Intrauterine fetal hypoxia

· Postmaturity (post-term pregnancy)

· Malpresentations (vertex, brow, face presentations)

· Transverse or oblique lying of the fetus

· Active maternal herpes simplex virus infection

· Fetal anomalies, such as hydrocephalus, that would make successful vaginal delivery unlikely

· Prolapsed umbilical cord in cephalic presentation

· Intrauterine hemolytic disease of the fetus

· Prolapse of the umbilical cord

· Maternal agony and a viable fetus (a healthy fetus may remain alive in 10-15 minutes after mother’s death)

· Maternal indications include:

· Extreme degree of pelvic contraction (the 3rd and 4th with true conjugate < 7 cm)

· Cephalopelvic disproportion (clinically contracted pelvis)

· Total placenta previa, vasa previa

· Abruptio placentae in case of no possibility for urgent termination of labor through the maternal passages

· Threatened rupture of the uterus

· Blockage of the pelvis by large or impacted tumors

· Extreme cicatricial deformation of the cervix

· Cancer of the cervix

· Pelvic tumors

· Pathological changes in the uterine wall (scar tissue in case of its incompetence)

· Hemorrhages due to incomplete placenta previa

· Severe preeclampsia

· Cervical rigidity

· Abnormalities of labor pains, without any effect of medicamental treatment

· A compromised history (cesarean section, antenatal intrauterine death of the fetus, infertility, extracorporal fertilization, the first labor at the age of over 30, etc. )

· Rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulae

· Decompensated extragenital diseases (or high risk of decompensation)

· Previous extensive pelvic floor repair (after the third-degree of tear)

· Varicosis of the vulva.

Sometimes the combined indications are also distinguished. These include indications, which are separately not sufficient enough to be an indication for the operation, but in case of their combination the better way of delivery for mother and her fetus is abdominal. For example:

· Premature rupture of amniotic membranes and expulsion of fluids, inefficiency of inducing the uterine contractility.

· Aged primipara with complicated anamnesis (primary infertility, mortinatality, etc).

· Aged primipara and breech presentation, or post-term pregnancy, etc.

· Breech presentation (or transverse lying) of the 1st fetus when there is multiple pregnancy.

· Contraindications for cesarean section include the following:

· When the child is dead or in such danger that there is very little chance of its survival.

· When there is gross infection of the maternal passages (endometritis, high temperature, any inflammation, more than a 6-hour period of ruptured water bag, more than 5 vaginal examinations during labor.

· Mother (or family) does not agree to the operation.

· Unskilled operators.

It is necessary to know that contraindications are of no importance in case of absolutely indicated operation (for example, severe hemorrhage, threatened rupture of the uterus, etc. ).

In case of high risk of inflammation after cesarean section (long period of ruptured membranes, a lot of vaginal examinations) one should choose one of the protective methods of operation.

Anesthesia. General anesthesias with pulmonary ventilation, segmental epidural anesthesia are commonly used. Local infiltrative anesthesia may be applied but very rarely nowadays.

Prerequisites for operations are:

· Child is alive and viable. (In case of severe hemorrhages, or absolutely indicated operation they are of no importance).

· Maternal agreement to operation (if there are no vital indications).

· Evacuated maternal bladder.

· Absence of any signs of infection.

Preparation for the operation

If cesarean section is going to be performed according to plan, it is necessary to give the patient light lunch the day before and only tea with some sugar overnight. Guidelines recommend a minimum preoperative fasting time of at least 2 hours from clear liquids, 6 hours from a light meal, and 8 hours from a regular meal. However, patients are usually asked not to eat anything for 12 hours prior to the procedure.

In the evening before the operation evacuant enema should be done to empty the rectum, and then sedatives are usually administered.

In the morning the enema should be repeated 2 hours before the operation. The bladder should be catheterized just before the operation.

The operation should be performed with the rules of asepsis and antisepsis.

Risks. The patient should be counseled about the standard risks of surgery, such as discomfort, bleeding that may require transfusion, infection, and damage to nearby organs.

|

|

|